By Molly Papows

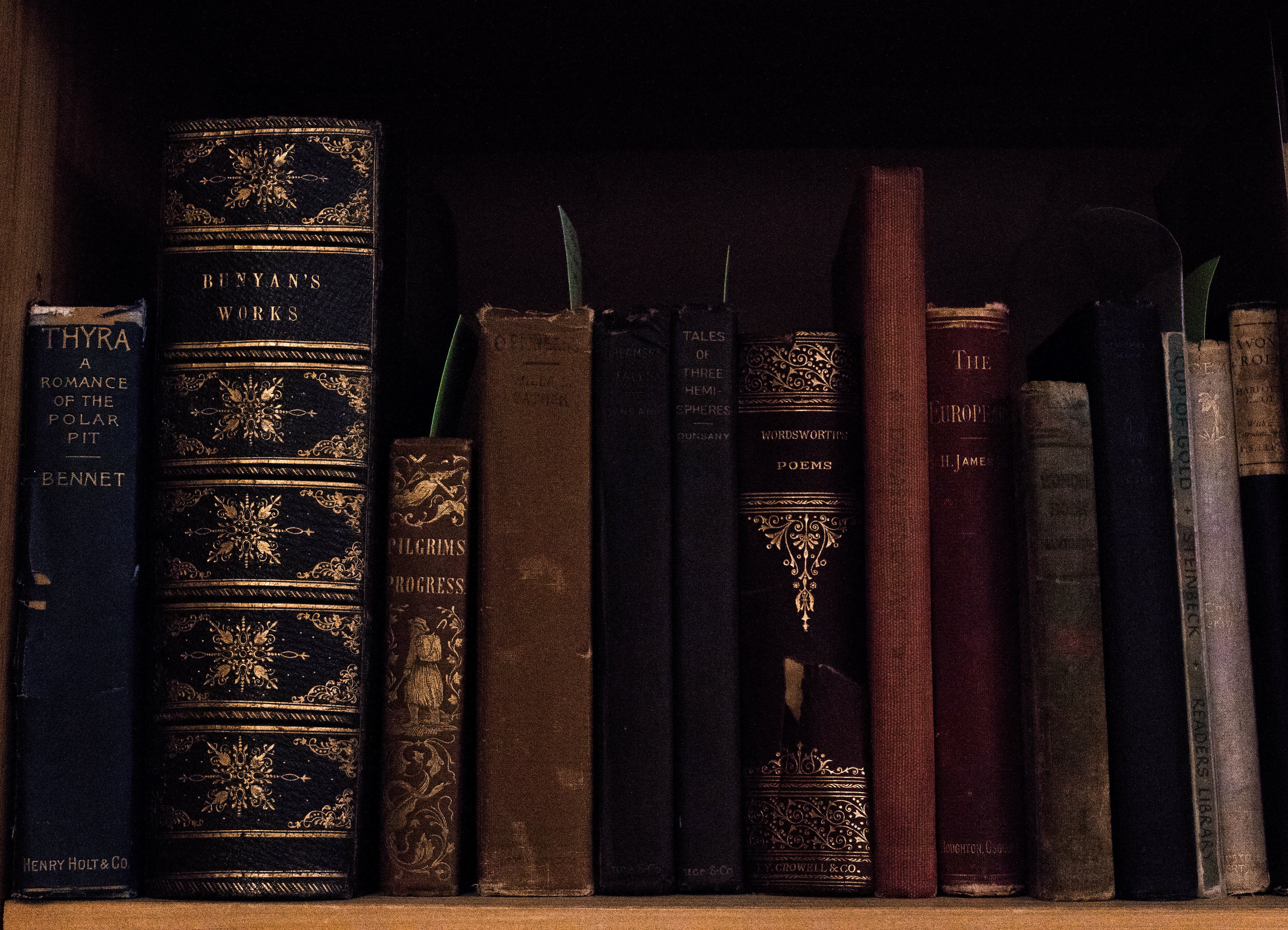

Used bookstores are as familiar as they are endearingly strange—you know what to expect because you don't know what to expect, and I didn't realize how much I'd missed that feeling until my eyes readjusted to scanning shelves of mismatched bindings instead of a screen. There's something insanely comforting about the sight of a row of hardcovers balanced on a windowsill. You can stand in the middle of Hanover’s Left Bank Books and see Collis, Baker-Berry, and the Dartmouth Green through those same elegantly tall windows—it's a little like standing in a crow's nest built entirely of books.

Rena Mosteirin became the owner of Left Bank this July following Nancy Cressman's thirteen years with the store. Rena is a published author, experimental poet, Dartmouth lecturer, and editor for Bloodroot Literary Magazine, and she understands that the store belongs to the Upper Valley as much as it belongs to her. She believes so much in the irreplaceable role a used bookstore plays in its community—especially a rural college community—that she took the helm in the middle of a pandemic.

Rena is extraordinarily intentional and generous in her approach to stewarding Left Bank. It's incredible to watch a new business owner capably navigate the harsh realities of the moment while taking joy in rearranging book displays and speaking with unguarded optimism about the kinds of encounters she hopes to facilitate. One moment we’d be chatting about her decision to close down the store in order to protect at-risk customers when Dartmouth students were in quarantine at the start of term, and the next she’d be effortlessly honing in on exactly the kind of novel I've been craving—even now my newly purchased copy of Renata Adler's Speedboat is tempting me when I should be writing this. It all felt reassuringly ordinary despite our masks and careful social distancing. Walking back outside after spending the morning with unfamiliar titles, gilded spines, photo books, and gorgeously illustrated maps broke the warmth of the bookish spell I’d been able to lose myself in for a moment, but I left full of excitement for the day we'll all be able to cram into that room together for a reading or a concert. Spaces like Left Bank are where we meet weird, wonderful, undiscovered facets of ourselves, and we'll need them more than ever when we come out on the other side of this thing. In the meantime, they're an important lifeline.

Photo by Molly Papows

Molly Papows: You first came to the Upper Valley as a Dartmouth undergrad and have been back for years now as a writer, editor, and lecturer: can you tell me a little about your evolving relationship with Left Bank over the years? Did taking over the store feel like a natural extension of your identities as a teacher and an artist?

Rena Mosteirin: When I was an undergraduate, I didn’t have a car, so Hanover was the Upper Valley to me. At that time, we bought our textbooks at Wheelock Books and otherwise had the Dartmouth Bookstore and Left Bank. Sometimes I would walk over the bridge into Norwich and go to events at the Norwich Bookstore. Dartmouth often brought superstars to campus, and they would read to packed auditoriums. While I was impressed by the big-name authors and loved the energy of huge events, I found the smaller, more intimate readings were often more interesting. People didn’t come prepared with questions designed to make themselves sound smart, you know? I hate that, because it doesn’t feel true to the moment, to the experience we all just shared listening to someone read from their work. I like when a Q&A is funny or weird. I like when questions introduce new ideas, but I love when it’s personal. When it’s a conversation that could only be happening at this moment in Hanover, New Hampshire with this group of people.

Teaching poetry workshops to graduate students in the Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies (MALS) program means I’m responsible for fostering a key part of their grad school experience: learning how to be good literary citizens. One of my goals with Left Bank is to broaden the scope of their literary lives while they’re here. I always tell my students to check out and follow Literary North and go to as many events as they can. I encourage them to submit to our local literary magazine, Bloodroot. When we can safely gather again, I hope to have grad student events and open-mic nights regularly, not just for MALS students, but for graduate students across disciplines who are interested in creative writing. I’m the faculty adviser for a graduate-school wide group called Dartmouth Writers Society (DWS). This group helps connect all graduate students at Dartmouth, including the scientists, with writing and reading. I hope to use Left Bank Books to provide my students with opportunities to build community with their cohort, other graduate students, and with community members.

Photo by Molly Papows

Molly: What possibilities excite you when you think about being able to safely host events in the store again?

Rena: Left Bank is a really special place for events. The shop has all these gorgeous artistic touches designed by the former owner, Nancy Cressman, who is a visual artist. She painted the walls a deep crimson, which brings out the shine on the old gold bindings of the rare books. Nancy established a bird motif for the store, there are birds everywhere and even a clock that makes bird calls on the hour. At readings she would sometimes introduce the store before she introduced the speaker, especially when the subject matter was controversial. I remember her telling us that Left Bank Books is a nest, a safe space for all ideas and discourses. She held a small bird's nest in her hands as she spoke about safety and then put the nest in the center of the room. That’s the heart of this store.

I can’t wait to do in-person events again. I love readings, musical evenings, puppet shows, story nights, poetry workshops... I’m excited for all of it. Bloodroot readings are always incredible because they mix well-established writers with people who are publishing for the first time. When I was just getting started as a writer, I loved being part of Bloodroot. I met so many people through those readings and I’m so happy to be carrying on that tradition. But I can’t talk about Bloodroot without expressing my gratitude for the work of “Do & Do.”

“Do” Roberts and Deloris Netzband founded Bloodroot as a print journal for the Upper Valley. They were known as “Do & Do” and their creativity and hard work developed and supported the literary scene. After Do Roberts passed, Bloodroot ceased to appear in print and it was clear that the Upper Valley was missing something vital. I was part of the original group of people to revive Bloodroot digitally and I have served in the publisher/co-editor role for the past five years. Deloris Netzband passed in March of 2020 and the next issue will be dedicated to her.

Molly: In the age of smartphones and e-readers, why do you think we still have this impulse to collect books?

Rena: Books that you can stack next to your bed comfort you. Books that you put on a shelf in your office help you with your work or research by suggesting themselves to you when your eyes flicker randomly around the room. Books in common rooms of your home tell your guests something about you: maybe who you used to be when you bought that collection of Allen Ginsberg poems, or who you aspired to be when you purchased Woman-Powered Farm.

Photo by Molly Papows

Molly: Is there any one book in your personal collection that’s especially meaningful to you?

Rena: For the past eight years I’ve tweeted a line a day (in order) of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick. It’s fascinating to slow-read a book I love, every day developing my relationship with it a little bit more. At first I was only using the Norton Critical Edition, the one I bought in college, but then I began collecting copies of Moby-Dick, so now I have one in my office, one at the bookstore, and a few at home. It’s helpful to have different copies when thinking about editorial interventions.

Last summer my husband and I published Moonbit, a book of experimental poetry and literary criticism that makes poems from the code that took Apollo 11 to the moon, and reads the code as a literary text. That book is very close to my heart, partly because it began as breakfast-table conversation. We were both interested in the code when it became available on GitHub, and started to explore it in our own ways.

Right now Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116 is at the center of a project I’m working on, so I have a tiny little broadside of it tacked up on the bulletin board behind the check-out.

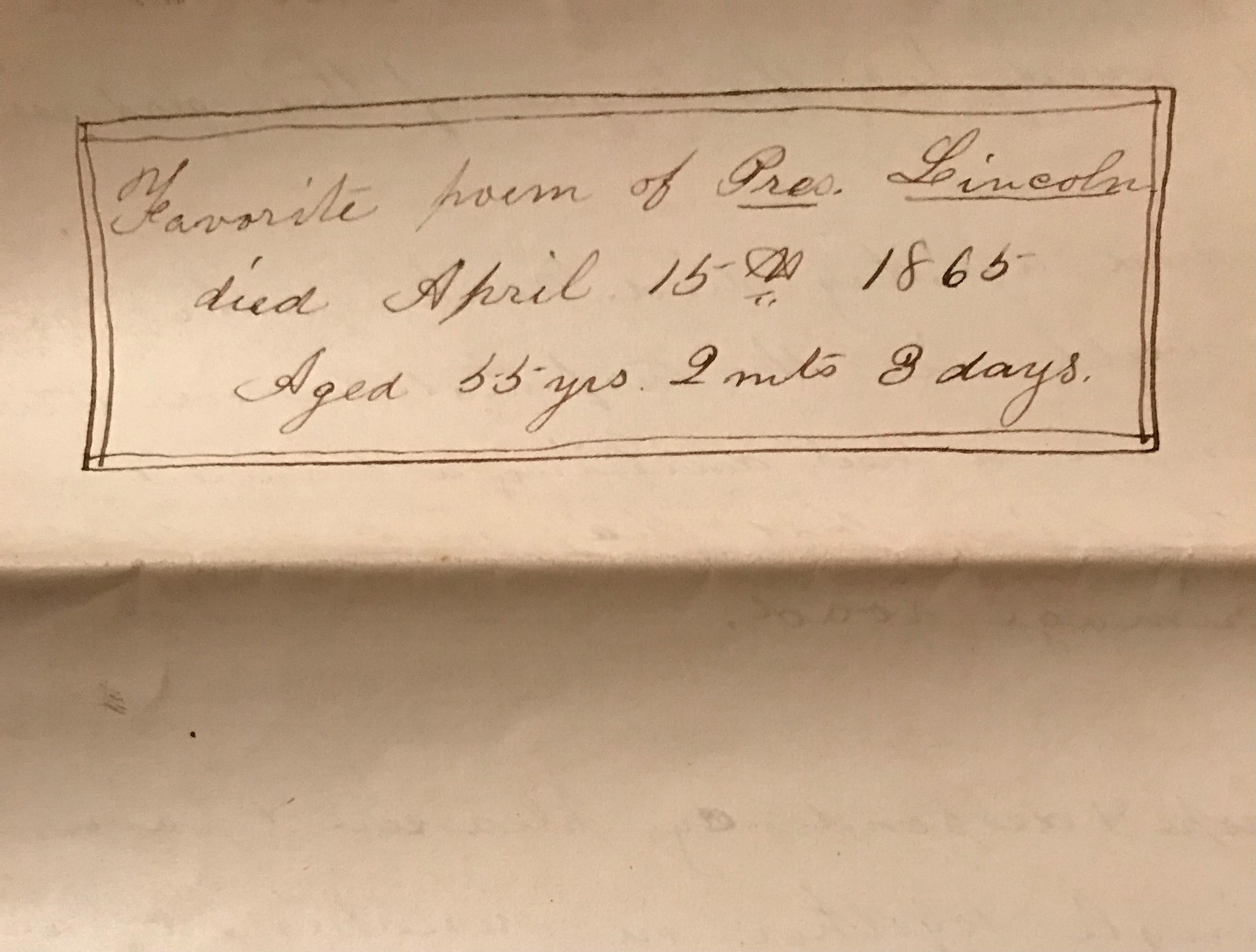

Molly: Do you stumble across many inscriptions when you’re processing stock, and do you have any favorites?

Rena: Frequently, when professors are moving out of their offices, they will donate boxes of books to us. I love when alumni come back and are browsing, say, the philosophy section, and find a book that belonged to a professor who taught their first philosophy class. Notes your professor made in a book they taught you are the absolute best marginalia.

I also have a thing for funny marginalia. Recently, I found a book where someone had scrawled in pencil: “Attention K-Mart shoppers: H to the Izzo!” Another simply said “Ass Man,” which I thought was pretty great. I found this weird little gremlin/cat face that just says “you” under it. Then there are some truly special things that get tucked into books, an invitation to the inauguration of the 10th president of Dartmouth College and a handwritten poem that purports to be President Lincoln’s fave.

Photo by Rena Mosteirin

Photo by Molly Papows

Photo by Molly Papows

Molly: That’s another part of the joy in owning a book—a well-loved one accumulates small personal histories over the years. Maybe someone wrote you an inscription when they gave it to you. Maybe you’re the kind of reader who takes notes in the margins. I came across a long-forgotten note from my grandparents in an old favorite just last week, and I love finding old concert stubs and train tickets and embossed cocktail napkins tucked between the pages I knew I would want to find again. The essay collection I was reading in early March has a receipt from a falafel place in Portland, Maine—dated just a few days before the lockdown—for a bookmark. I’m not someone who’s ever kept a journal, but man, that scrap of paper snaps me right back to what I was thinking and feeling in that moment, both within the world of the book and outside of it. I think Michael Ondaatje was paraphrasing a 19th-century novelist when he wrote “a novel is a mirror walking down a road,” and I believe that sentiment to be true in more ways than one—the book as story and the book as physical artifact—though I guess that’s also an awful lot to hang on an old falafel receipt!

When you’re revisiting a poetry collection to teach or picking up Moby-Dick every day for your ongoing project, are you also finding windows into different times in your life?

Rena: Yes, that happens all the time! Recently I went looking for my old copy of the Bhagavad Gita and found a flyer inside from a Take Back the Night rally I attended in Washington Square Park in 2006. I remember being at that rally and being approached by these friendly Hare Krishnas in their saffron and crimson robes. They gave me the book. I used the flyer as a bookmark and didn’t really think about that night again until I was using the book for an Independent Study and I was like, oh yeah, that rally… was that really fourteen years ago?

I also love finding bookmarks from bookstores I care about and when people donate books to Left Bank, I find bookmarks from places I’ve never been to, many that don't exist anymore. I like to imagine what these shops were like when they were thriving.

Photo by Molly Papows

Molly: I’ve had a few jobs that have required art handling, but I’ll never forget the day the paper conservators taught me how to manipulate wedges and weights and safely handle the illustrated books and manuscripts in the museum’s collection—it never stopped being completely terrifying and thrilling, and it gave me a whole new appreciation for books as objects. A centuries-old spine tells you how it wants to open when you read the tension under your fingertips just right, like listening for a harmonic on a slightly out of tune string. Are there any rare or out of print books at the store right now that you’re especially excited about?

Rena: Oh yes! I’m currently obsessed with this 14-inch first edition of Babar’s Visit to Bird Island, from 1952. The illustrations are incredible. Imagine elephant children flying on the backs of huge, strong, colorful birds, headed for Bird Island. When they’ve reached the island, the elephants and birds go to the ostrich racetrack. After the races, they feast under a lit canopy of lush green trees with their new bird friends; cranes, parrots, pink flamingos, ducks, pelicans, storks, etc... If I weren’t already a bird watcher, I think this book would convert me.

Another book I’m completely captivated by is our 1966 copy of Message from the Interior by Walker Evans. Each photograph is printed gorgeously and they tell a story of spaces, reflections, and details. Whenever a photographer comes into the store, I put this book on the back table for them to flip through and enjoy. I love when people want to look through our rare books and I try to make sure they know there is never any pressure to buy them.

Photo by Molly Papows

Molly: You took over Left Bank Books in the middle of a pandemic, and Allie Levy opened Still North Books & Bar just down the street three months before it hit. You seem to beautifully complement each other’s presence downtown. Can you speak a little more to the special role a used bookstore plays in its community?

Rena: Allie has been so supportive as I’ve learned the ropes of bookstore ownership. Honestly, I don’t know how I could do all of this without her. We call each other’s places “sassy sister stores” and are always sending customers from one shop to the other. We have different types of books but really similar philosophies: there’s so much great writing happening in the Upper Valley, and it’s full of supportive people. I think we both see our work as community building more than anything else.

So how are we different? Allie presents a well-curated selection of gorgeous new books at Still North in a stylish, fresh setting, and she sells books online. Left Bank allows you to browse books that have been previously owned by members of our community and we don’t do any online selling at this time.

I’m often asked why we don’t sell online. Sustainability is the key here: we don’t send our books out all over the world and they don’t come in on trucks. People donate them from their homes to our shop and then the books go back out into the community. It’s a very simple way of doing business that puts the planet before profit. Also, our books are a way of reading and understanding the community. What are your neighbors reading? Come to Left Bank and see!

Molly: Yes! You spoke earlier about the funny, honest conversations that tend to spring out of those more intimate readings in a space like Left Bank, but I think that also applies to the books you discover while you browse, and the circumstances and community that make that possible.

It’s an extraordinary moment to be a new business owner, and I’ve been so struck by the way area businesses and organizations have supported each other throughout the pandemic. Has your experience so far given you a new perspective on the Upper Valley, and on the literary scene here?

Rena: Literary North is the beating heart of the literary scene in the Upper Valley and beyond. Reb and Shari have been so supportive. They’re absolutely amazing women, both of them are brilliant writers, and their website is a goldmine. If you’re not getting their newsletter, I encourage you to sign up.

I recently joined the board of the Frost Place in Franconia, New Hampshire. Frost Place is Robert Frost’s old homestead that’s now a non-profit educational center. Previously, I went to Frost Place for readings and as a conference participant, but now I’m seeing this whole other side, getting to know the people responsible for keeping it going. Robert Frost’s legacy is such an important part of New Hampshire’s cultural heritage and it’s an honor to be part of a group of people intent on preserving that.

Michael at Robert’s Flowers of Hanover makes the most gorgeous arrangements and I like to feature them on the table in the middle of the store. Since I took over the shop in July, the center display has only had one theme: Black Lives Matter. Michael’s floral creations draw your attention there and honor the work of our featured Black writers.

We are in the midst of such challenging times, but I love our community more than ever. We are being brave, we are speaking up, we are voting, we are making art, we are writing, we are reading. I feel so lucky to live here, to call the Upper Valley my home.

I recently joined the board of the Frost Place in Franconia, New Hampshire. Frost Place is Robert Frost’s old homestead that’s now a non-profit educational center. Previously, I went to Frost Place for readings and as a conference participant, but now I’m seeing this whole other side, getting to know the people responsible for keeping it going. Robert Frost’s legacy is such an important part of New Hampshire’s cultural heritage and it’s an honor to be part of a group of people intent on preserving that.

Michael at Robert’s Flowers of Hanover makes the most gorgeous arrangements and I like to feature them on the table in the middle of the store. Since I took over the shop in July, the center display has only had one theme: Black Lives Matter. Michael’s floral creations draw your attention there and honor the work of our featured Black writers.

We are in the midst of such challenging times, but I love our community more than ever. We are being brave, we are speaking up, we are voting, we are making art, we are writing, we are reading. I feel so lucky to live here, to call the Upper Valley my home.

November 2020

Photo by Molly Papows

Left Bank Books is open 9:30 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. Wednesday – Saturday, and noon – 4:00 p.m. on Sunday. While they’re not buying books at the moment, they are accepting book donations.

Rena J. Mosteirin is a Latinx experimental poet, publisher of Bloodroot Literary Magazine, teacher at Dartmouth College, and owner of Left Bank Books. Mosteirin’s novella nick trail’s thumb (Kore Press, 2008) was selected by Lydia Davis for the Kore Press Short Fiction Award. Her chapbook half-fabulous whales (Little Dipper, 2019) explores Moby-Dick through erasure poetry. She is the co-author of Moonbit (punctum books, 2019), an academic and poetic exploration of the Apollo 11 Guidance Computer code.

Molly Papows is an art historian based in Lebanon, NH. She has an MA in the History of Art and Architecture from Boston University and ten years of experience working in encyclopedic fine art museums. She's also interested in the many ways an artist can tell a story across disciplines — from fiction and nonfiction to poetry, landscape architecture, and music.

Photo by Molly Papows