By Courtney Cook

(A version of this essay appeared in the weekly newsletter, Survival by Book)

Last week, my colleague and I met online to put together the slide deck for our team's last operations review before Thanksgiving. We got started pretty late in the day, so my colleague’s kids had started to make their now familiar, end-of-workday video cameos. One of his daughters came in for a brief, sideways snuggle, laying her girlish arm across his back and fluttering her tiny hand against his shoulder. His other daughter, more camera-shy, could be heard speaking from out of view. His small son presented himself with a request—for a snack or to complain about his sisters, I can’t remember which—and then for a snuggle that started as a side hug but evolved to clambering into his dad’s lap. Lately, this intrepid kindergartner has been investigating what are the rules for acceptable behavior in front of the people on his dad’s computer screen: is it ok to say poopy pants several times in a row? Only time will tell.

One of the things I have liked about working from home these past months are these homely moments that are revealed in video conferences. Part of my job is meeting online with people in Brazil, India, the Netherlands, Poland, and other countries and, now that we meet from our homes, I look forward to the quick chats about the art, books, and memorabilia that can be seen in their backgrounds. The now-reliable child and pet cameos that happen in meetings has built even more empathy and affinity. It helps that every single one of us feels a sense of solidarity about our global common cause against Covid-19.

Photo by Courtney Cook

The importance of these small intimacies is much on my mind this week, because, for me, Thanksgiving is often as much about loss as it is about plenty. This comes from how lovely and uncomplicated Thanksgiving is as a holiday; it’s easy to make it special no matter where you are or whom you are with. I had many, very happy, Thanksgiving memories as a child, which sets a certain expectation for joy right out of the gate. And, then, as an adult I had many happy iterations on the holiday as my family and I celebrated it in various places and with different combinations of friends and family.

It’s a memory-cornucopia that is tinged, a bit, with the fact that some of the people with whom I shared these memories are gone now: some are no longer alive and others are no longer in my life in the same way. I miss them. I miss the times we had back then. Which is where the annual practice of gratitude comes in. I have found that gratitude isn’t bound by time or place and that, when I practice it retrospectively, it shifts memories out of binary categories like “good” and “bad” and into multi-layered patterns of experiences that are evocative of things more like “strength” and “sense of self.”

The way my memories have formed into a source of resilience is one of the few things I have loved about getting older. The poet (and Dartmouth alumni) William Bronk writes,

What the vision is sure it sees

is a whole new world, a better one by far,

or perfect, in the shape of desire. The heart believes,

and then comes back to believe again; it has to believe

while desire holds.

There are so many visions for my heart to believe in.

It was the first November after I moved back to the Upper Valley when I discovered the Thanksgiving week Norwich Farmer’s Market. Held in its winter quarters inside Tracy Memorial Hall, it is the peak harvest and holiday experience—all of the best of the growing season paired with all of the best of the season of carols, candlelight, hot cider, and cheerfully hand-knitted mittens. It's been a part of my Thanksgiving celebrations ever since.

I love everything about this event. I love how Tracy Memorial Hall is the exact right combination of Georgian Revival meets Yankee town square with its lofty ceiling and molded cornices paired with plain board floors and large, plain windows. I love the egalitarian plenitude of the market, too, how the heaped vegetable stands take pride of place along the outer perimeter, and the purveyors of pickles, herbs, meats, empanadas, and cheeses fill in the center and spill out into the basement and even to the sidewalk outside.

photo by Courtney Cook

Last year, I went with a friend, and we talked our way through the main hall and the basement, catching each other up on our lives, chatting up vendors, and greeting local acquaintances in one seamless conversation. We ended up on the stage area in the hall where we visited the coffee cart and griddle sandwich people while greeting the market’s director, Steve Hoffman, who, as he says, gets to throw a party for the Upper Valley every week.

On our way out the door, we stopped to buy cups of delicious Norwich Creamery hot chocolate, and I added a wreath from the Spruce Lane Farm booth to my market haul. I came home with everything I needed for Thanksgiving week cooking, plus the day’s impulse buys: honey and a beeswax candle from a local apiary and wool dryer balls and a knitted hat to add to my admittedly large collection. As I carried my many treasures back to my car, I reflected on how great it was to know that every dollar I had spent had stayed local.

photo by Courtney Cook

photo by Courtney Cook

photo by Courtney Cook

When I delve deeper into the cornucopia of Thanksgiving memories, traveling through time to my Wyoming childhood, I see holidays spent around my grandparents’ dining room table. Heavy and intricately carved, able to seat twelve adults comfortably, and set with creamy linens and shining glassware, including a pair of tiny, rose-shaped salt and pepper shakers for every place setting, the table was the magnificent center of a decades-old tradition. On Thanksgiving morning, my grandfather—Boppa—would call to see if we were watching the Macy’s Day Parade. In the afternoon we’d go down to his and my Bomma’s house to gather with assorted aunts, uncles, friends, and cousins over an enormous turkey with all of the traditional accompaniments, including, but not limited to, homemade rolls, canned cranberry sauce, turkey gravy that could not—must not—have any lumps, and that green bean casserole made with cream of mushroom soup and canned crispy onions. And pie. Of course there was pie.

My grandparents’ house was full of wonders: closets large enough for children to play in and filled with dresses, hats, and shoes from the 1950s and 60s; shelves of books in all four of the bedrooms; my grandmother’s costume jewelry; a whole drawer in the kitchen that was just for candy; an actual pump organ that emitted something akin to musical tones when we managed to work its pedals; and a large, drafty basement lined with gun racks and duck decoys, and stocked with vintage puzzles, games, and a 1950’s style bar area in which we played “store.”

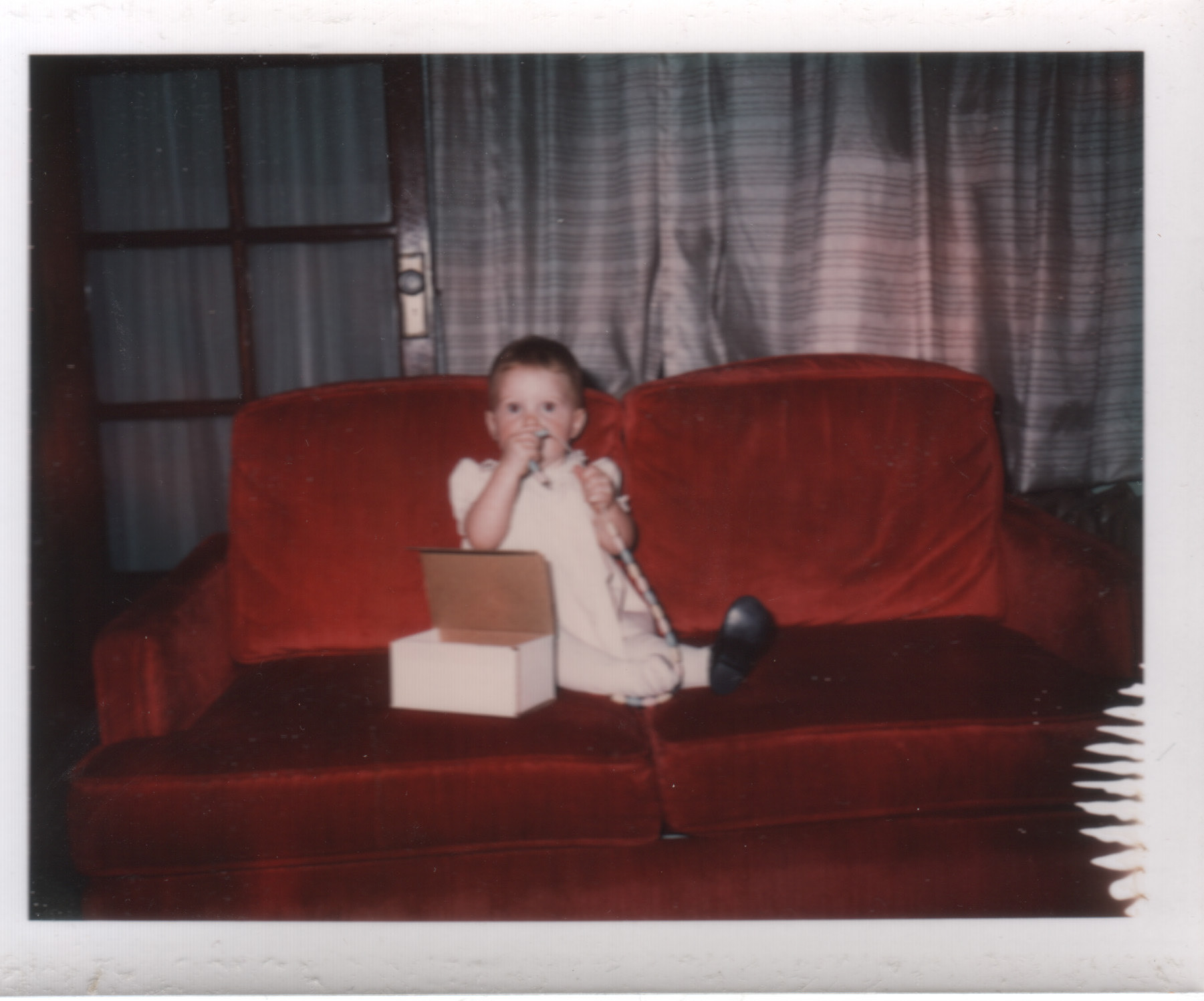

When I got tired of the hubbub, there was a kid-sized red velvet couch in the corner of the living room, perfect for escaping into the pages of a book while still being near the comforting sounds of late-day, family revelry.

The thing I miss the most about these holidays is the number of people who were assembled. Holidays since—even happy ones—feel a bit skimpy when there are just four or even six people. The houseful at my grandparents' set the bar high when it comes to what feels truly festive.

Photo by Willard Cook

Photo by Willard Cook

Turn the memory dial forward a decade and a half and set it to the other side of the world, and the vision I get is Thanksgiving in Australia in the late ’90s, hosted by Aussie friends who promised an “American-style” event, albeit we had to have it on the third Friday of November because no one had the actual Thanksgiving day off from work.

What exactly constituted American-style was highly subjective, even between guests. For our host, who was and is a phenomenal cook, it meant serving grilled sea bass that she had got that same day at the Sydney Fish Market and various other accompaniments, most of them based on fresh ingredients that seemed to just fall off of trees in that bountiful ecosystem. There was even a nod to pumpkin pie, but since pumpkins in Australia are the vegetable we Americans refer to as squash and not meant to be eaten as a sweet, it was more like a savory pudding. We gathered for this meal outdoors around a long table under a terrace—it was, after all, late spring in Australia.

Meanwhile, many of the Australian guests came in costume, or, as they called it, “fancy dress.” They had either conflated Thanksgiving, a holiday in which Americans eat pumpkins as pie, with Halloween, a time in which pumpkins are carved, or they thought that they should come dressed as Americans to an American-themed dinner. My favorite was the couple who came as George (Herbert Walker) and Barbara Bush. They were especially realistic because when Australians try to do an American accent, they sound Texan.

Photo by Mel Geyer

It's stunning to realize that an Australian-American Thanksgiving celebration in fancy dress and on a Friday night during the lush Sydney spring looks more normal than what I’m looking at this year. It feels like everything but the date is different.

This year, the Norwich Farmer’s Market was outside at its summer location, and I didn’t go, wary as I was of the governor’s escalating warnings about social distancing. I don’t even know if the Norwich Creamery guy was there, selling his best ever hot chocolate. This year, there will be no large gathering of family members in Wyoming, nor even a small group of cousins. For me, there will be no Australians, no life partner, no visit with my sister and her family, nor even my own children. This year, even my grandmother’s big table, now ensconced at my aunt’s Wyoming ranch, will be set for just two people.

And yet . . .

On Saturday, while I was running an “essential errand” in Hanover, a store keeper asked me “what are you doing for the holiday” while he was ringing up my purchase. I stuttered a bit, not wanting to say the truth, which is “nothing.” Then, in the space that the awkwardness created, we both started to laugh. “I can’t break myself of the habit of asking the question,” he said ruefully, “but we all have more or less the same answer. Anyway, it won’t last forever.”

In that moment, there it was again--that sense of solidarity that I have been tracking for months now as I adjust to the ever-changing rules of human interaction. It is a powerful sense of recognition that says no matter who we are and what our lives used to look like, we are in this thing together.

I love the word together so much right now. What a remarkable and blessed irony it is to feel so connected even while continuously socially distanced.

Last week, probably because it was late in the day and we were loopy from a busy week, my colleague and I decided to add some Thanksgiving flair to our PowerPoint presentation. By the time I joined the meeting, he had already added photos of turkeys, alive and roasted, pumpkins, on the vine and baked into pies, and corn, in sheaves and on the cob, to the transition slides. We then set about turning our team’s editing partnership into an eating partnership and a code rebase into a rebaste and then into a re’baste. We added pass the pie to a slide heading, and then changed it to pass the pie, pilgrim. We even made a slide called, simply, “Tryptophan Break." The more we added, the more we giggled. When we couldn’t come up with anything more clever, we just typed the phrase gobble, gobble somewhere on the slide and laughed harder.

The fact is, one of the things I'm most thankful for this year is my colleagues. Our daily meetings are an important part of my life now, alongside socially distanced walks with my neighbors, voice texting with my sister, video calls on the porch with friends, and Zoom meetings with my mom and dad. That silly, turkey-themed PowerPoint presentation was on the surface just a throwaway moment in a busy week, but it’s also taken on symbolic resonance in the quantum dimension of my Thanksgiving holidays. The heart believes/and then comes back to believe again. Memories are not hierarchical; even the tiny good ones make a difference.

I haven’t even roasted this year's twelve pound turkey yet, but I already know that the best thing about Thanksgiving 2020 will be the way it showcased an abundant, collective, human resilience.

November 2020

Courtney Cook is a writer based in Wilder, VT. She has degrees from Dartmouth College and the University of Wollongong, Australia, taught English literature for ten years, and now works as a technical writer and marketing manager. You can read her writing at the Los Angeles Review of Books and in her weekly newsletter, Survival by Book.