By Colleen Goodhue with additional reporting by Isaac Lorton

Earlier this summer, two white men in a blue Toyota took an evening joy ride through Bethel and Royalton, Vermont. They threw beer bottles and cans out of their car and yelled “racial comments” to passerbys, according to the constabulary report.

When asked if they were anti-white or anti-Black comments, Bethel Constable Oscar Gardner replied, “It was neutral based. They said something to the fact that ‘Black Lives Don’t Matter. White Lives Matter.’ Something to that effect, but you can take it however you want.” He described it as a littering charge, not a racist incident. “I have never heard of any racial issues in Bethel,” Gardner says. “It’s your typical Vermont town.”

Vermont is about 94% white. Its small towns are often even more homogeneous than the cities. Racism can feel like a non-issue to white residents; they turn a blind eye to the vandalization of Montpelier’s Black Lives Matter mural, the presence of racist graffiti and Nazi flags, Kiah Morris, a Black lawmaker in the Vermont Statehouse, resigning due to racist harassment, and the many other micro- and macro-aggressions Black Vermonters encounter every day. If you don’t see a problem affecting your community, it can be easy not to get involved and, for many, it can seem like racism doesn’t exist in Vermont. Bethel resident and owner of Hustle & Loyalty Records David Phair says, “I can tell you first hand that it does.”

Phair was born in Connecticut, but moved to Vermont as a young child when he was taken from his mother and placed into foster care. Over the next thirteen years, he says he was placed in 17 different homes; David is Black and all of his foster parents were white.

At first, Phair didn’t recognize the racism in his new life in Vermont. “I was different, but didn’t know why,” he says. “You grow up hearing these jokes that God left you in the oven a little too long. As a five year-old-kid, that made sense.” As he grew up, he began to see it more and more. “It wasn’t shoved down your throat, but there was an obvious racist presence in the state.” There are coded symbols and language that are not easy to identify: like the Confederate flag often flown outside homes and seen on bumper stickers. To many, it’s an obvious sign of white supremacy, but out in the country some claim it's a symbol of rural heritage. Phair admits that he even flew the rebel flag for a bit, before understanding the message behind it. “I think the hardest thing to do was growing up and opening my eyes to it.”

Vigil for George Floyd at Babes Bar on Tuesday June 2. Photo courtesy of Owen Daniel-McCarter.

On May 25, George Floyd was killed by now former-Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin while three other officers stood by doing nothing. The incident sparked off a nationwide call for racial justice, defunding police, and anti-racist activism. In his predominately white hometown, Phair felt all eyes turn to him. “I have a history of doing public speaking. I felt obligated,” he says. “As far as the community sees, there’s me and one other [Black] guy and if we aren’t going to speak up for ourselves, who is?”

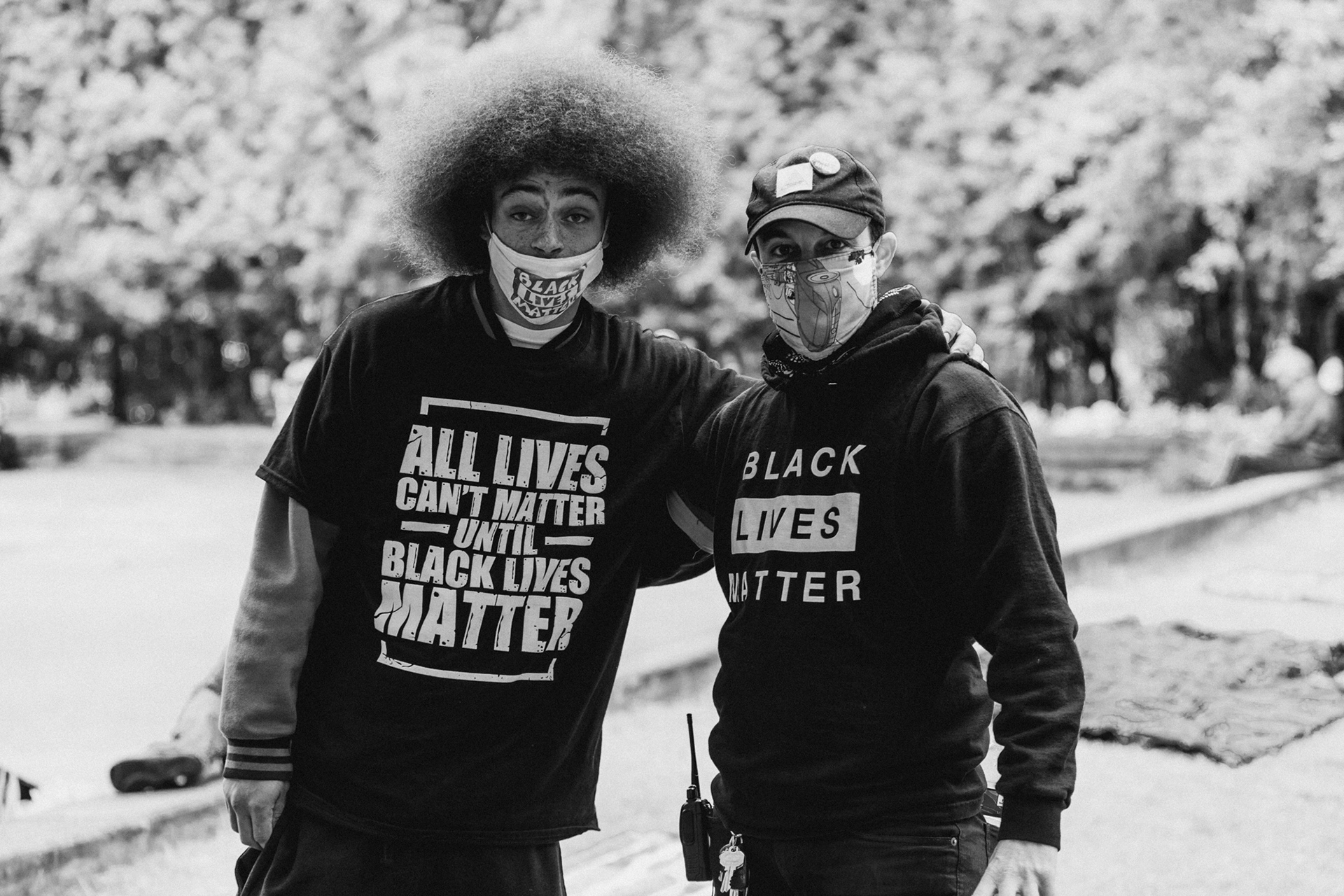

As demonstrations began across the country, Phair began organizing a rally in Bethel for June 13; he contacted town officials and got in touch with police. He also talked to Owen Daniel-McCarter and Jesse Plotsky, owners of Babes, the bustling and inclusive-of-all bar in the center of town. They had met two years prior when the couple were still hanging up the sign for the newly opened bar and Phair came to greet them. He was a huge supporter of the bar from the getgo and they decided to collaborate on a monthly hip-hop night with Hustle & Loyalty Records, the record label Phair had started to support people struggling with addiction.

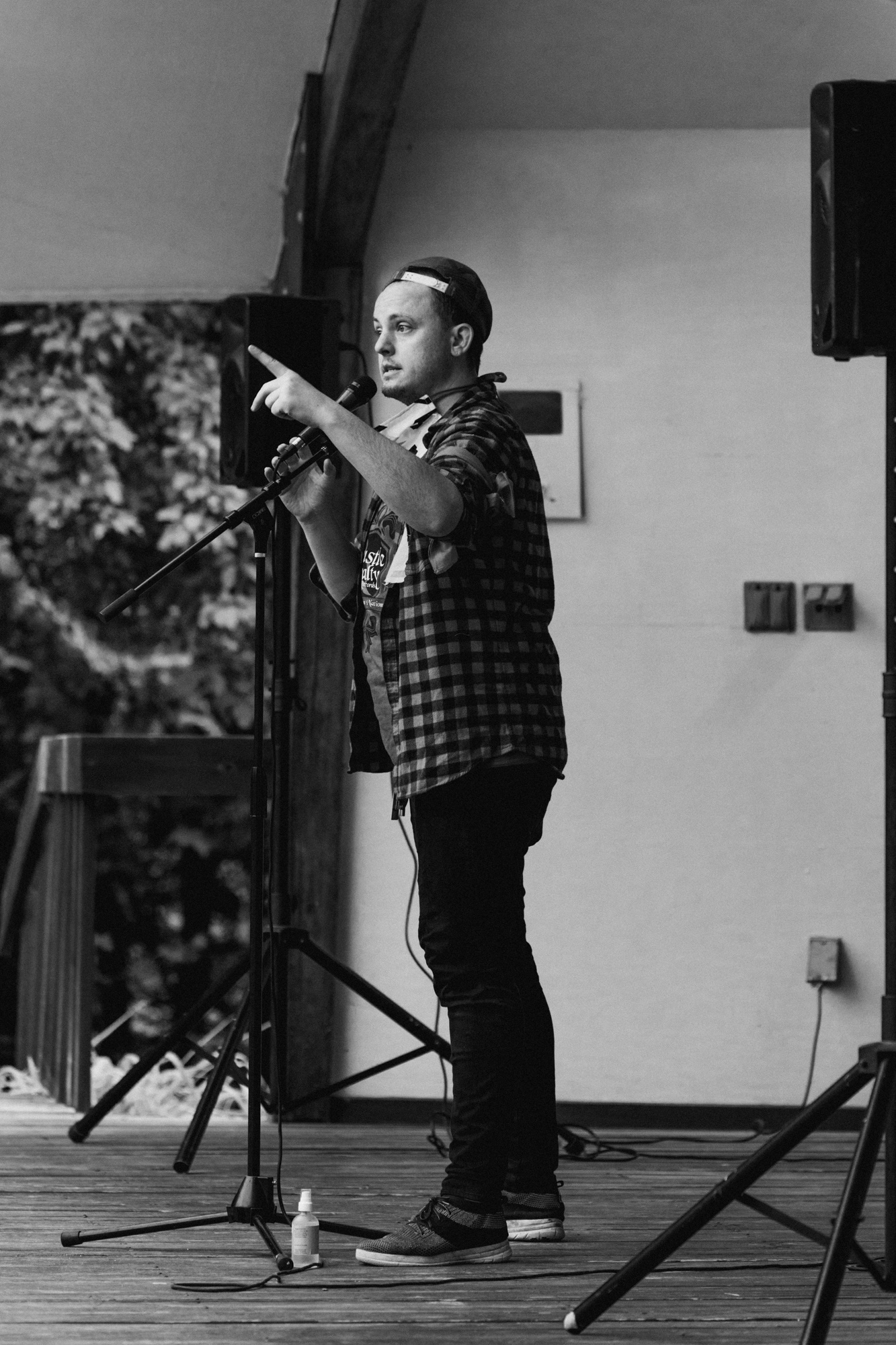

Owen Daniel-McCarter. Photo courtesy of Nick Keating.

David Phair and Jesse Plotsky. Photo courtesy of Nick Keating.

Before it opened, there were rumors that Babes was going to be a gay bar, but the owners made it clear it was a bar for everybody. Daniel-McCarter says that they wanted Babes to “model what a space looks like that is centered on traditionally marginalized folks and oppressed people in our country.” Their choices in artwork, the books in their library, and the gender-neutral bathrooms are meant to center women, people of color, and queer people. The bar has been a welcoming environment for people from all walks of life and the owners welcome tough conversations. When the pandemic closed the bar, they felt it was a missed opportunity to have conversations about race within the bar’s community.

“For us, bars are always a site of organizing,” Daniel-McCarter says. “I love going to bars and I also love going to queer bars, which are fundamentally – at least historically – activist spaces and spaces where the physical presence of being out and being queer is an act of resistance.”

The couple moved to Bethel from Chicago where Daniel-McCarter had been a lawyer; he often served as the on-call lawyer for marches and protests. He says, “I was always very involved in the planning of the marches from the perspective of permitting, managing the cops, and stuff like that – so for me, I was like, ‘If you have the vision, I have a lot of experience in training people to support that vision.’” The trio began planning not just the June 13 march, but also a more immediate vigil for George Floyd on Tuesday, June 2 outside the bar. “I honestly couldn’t believe it,” Phair says. “We announced we were gonna do it and did it the next day. There were over 250 people that showed up.”

Vigil for George Floyd. Photo courtesy of Owen Daniel-McCarter.

Vigil for George Floyd. Photo courtesy of Owen Daniel-McCarter.

Attendees laid flowers and candles at the memorial, which featured photos of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Nina Pop, and Tony McDade. Breonna Taylor was a 26-year-old emergency room technician who was killed by Louisville police officers who entered her home with a no-knock warrant. She was shot while lying in bed. Nina Pop was a 28-year-old trans woman of color who was stabbed to death on May 3, making her at least the 10th transgender or gender noncomforming person violently killed in 2020. Tony McDade was a 38-year-old Black trans man who was killed by police on May 27.

At the vigil, Phair says, “I spoke separately to the Black and white crowd. I told the Black crowd that we have to speak up and let our voices be heard and to the white crowd, you have an obligation to listen and turn around and speak to the other white people. [The message] comes across differently from a white person to a white person.”

Daniel-McCarter remembered, “This minister from Woodstock came up to me afterwards and says, ‘It’s like you’re holding church.’ And then he was like, ‘I remember a lot of radical movements are either supported by churches, bars, or both.’” Eleven days later, on June 13 they held the Bethel Rally & March for Black Lives at the Bethel Bandshell. Phair remembers that when they first arrived at the bandshell, he didn’t see anyone and started to get nervous. Then dozens of volunteers showed up to help with parking and merch tables and about a hundred attendees came to listen to the speakers.

The crowd listens to a speaker at the Bethel Rally and March for Black Lives. Photo courtesy of Nick Keating.

"To break it up, we played what I refer to as protest music—anything from Bob Marley to Pink Floyd to “Fuck the Police” to Tupac to anything with a meaning behind it. Babes Bar paid all the guest speakers," says Phair. "[Tabitha Moore of the Rutland NAACP] pointed out that people need to pay Black people for their services, from teaching you about race or how to play basketball, pay them for that. We may not get reparations and that means people should not provide services for free.”

After the rally, the crowd marched two miles from the bandshell to the South Royalton police barracks. The distance commemorated Ahmaud Arbery, the 25-year-old Black man who was killed by three white men while out for a jog. Phair recalls the remarkable size of the crowd, and watching people pulling over in their cars to join. “A guy was walking into his house and heard us yelling ‘Black Lives Matter’ and he said ‘Shut the fuck up’ and gave us the finger. We kept walking,” Phair remembers. When they reached the South Royalton barracks, he asked the men to lay on their stomachs for 8 minutes and 46 seconds in honor of George Floyd and for the women to lay on their backs in honor of Breonna Taylor. This is a demonstration commonly occurring a protests across the country, asking participants for a moment of silence to consider the experience of Black people killed by police.

Demonstrators marching through downtown Bethel. Photo courtesy of Nick Keating.

Phair says that the town has been very supportive, for the most part. Though he laments that the numbers for the march weren’t as high as he’d hoped. “I had four of my friends there. If I can only get four of my close personal friends to something this important, which side of the fence are they on?” In the month of June there was a flurry of support from white people. While some of the energy has died down, many activists and supporters are calling their communities to defund or abolish the police. David Phair thinks that the money from the town constabulary department (about $43,000 for FY 20-21) should be rerouted to youth sports or to the school debt. He runs a softball league for adults and wants to see the next generation of kids playing more sports than video games.

Babes Bar itself has a “No Cop” policy at the bar, perhaps a microcosm of what a community could look like without a police presence. “We never call the police,” Daniel-McCarter says. “The police never help a situation. They usually wind up arresting our clients, our staff, it always escalates in really harmful ways.” Instead they hold people accountable for their actions. They ask them to acknowledge harm they’ve caused to the community before allowing them back in the space.

“If you call the police, then it’s like cops take this person away. ‘Solved the problem’, which is apparently giving them an assault charge or something. Now they have a background. Now they’re angry. None of the root issues have been addressed. What I’m excited about is that because it’s been our model and those are the values and the experiences we came in with, we’ve trained our staff on that model, we’re training our staff on harm reduction and other things that now we get to say, ‘Hey, you, person that likes our bar but is really afraid of what it means to defund the police, guess what? It looks like our bar.’"

The Black Lives Matter movement protests police violence against Black people, an issue that many white people still do not see the intrinsic value in fighting for. Some of Babes’ white clients have told Daniel-McCarter their own intense stories about state troopers and local police, and he believes that combating police brutality can be a unifying point for some. “We just keep trying to reframe it as, if we end police violence centered on the people that experience it in the most hostile and historically violent ways, it’s going to solve it for all of us. We just need to really make sure we get to the root.”

It’s been over a month now since the Bethel Rally and March for Black Lives. Babes continues to hold events including a teach-in about the life of Elijiah McClain, a 23-year-old Black man who was killed by police on August 24 of last year. “There’s a lot of things that we’re going to work on that I’m really excited about. I’m really excited to keep working with David and others,” Daniel-McCarter says. “There’s a lot of things on the horizon, as well, and really thinking about the opportunity of the small community, the local town. Like really thinking about community accountability and defunding the police as tangibly very possible here. And really thinking about how we can model that. How we can be fundraising and shifting our resources to places where there are more Black folks on the ground organizing, being arrested? How can we be supportive of Black folks in other communities, as well as our own?”

Phair has two daughters who live in Connecticut. Despite any progress that might be happening, he says, “I would not want to raise a kid up here who is not white. As a kid it was very confusing.” Phair has had to change the way he interacts with friends and coworkers. Where once he’d felt fine making racial jokes, he pulls back from them now. His friends are also growing more aware of the struggle. In the past, they’d joke around with racial slurs they perceived as harmless, but he says, “they have cut back on that because they know what I’m fighting for.”

August 2020

Colleen Goodhue is a videomaker and writer living in West Lebanon, NH. She loves archives, long layovers, and all kinds of friendly competition. She performs with Valley Improv, the Upper Valley’s best and only improv troupe.

Special Thanks to Nick Keating for his photographs of the Bethel Rally and March for Black Lives.