By Molly Papows

Traveling musician Ben Cosgrove's essay A Space Filled with Moving is the second installment in Literary North's Little Dipper chapbook series. Upper Valley residents Rebecca Siegel and Shari Altman founded Literary North to advocate for New Hampshire and Vermont's rich literary arts community, and each Little Dipper book is hand-made in limited edition runs following a close collaboration with the author.

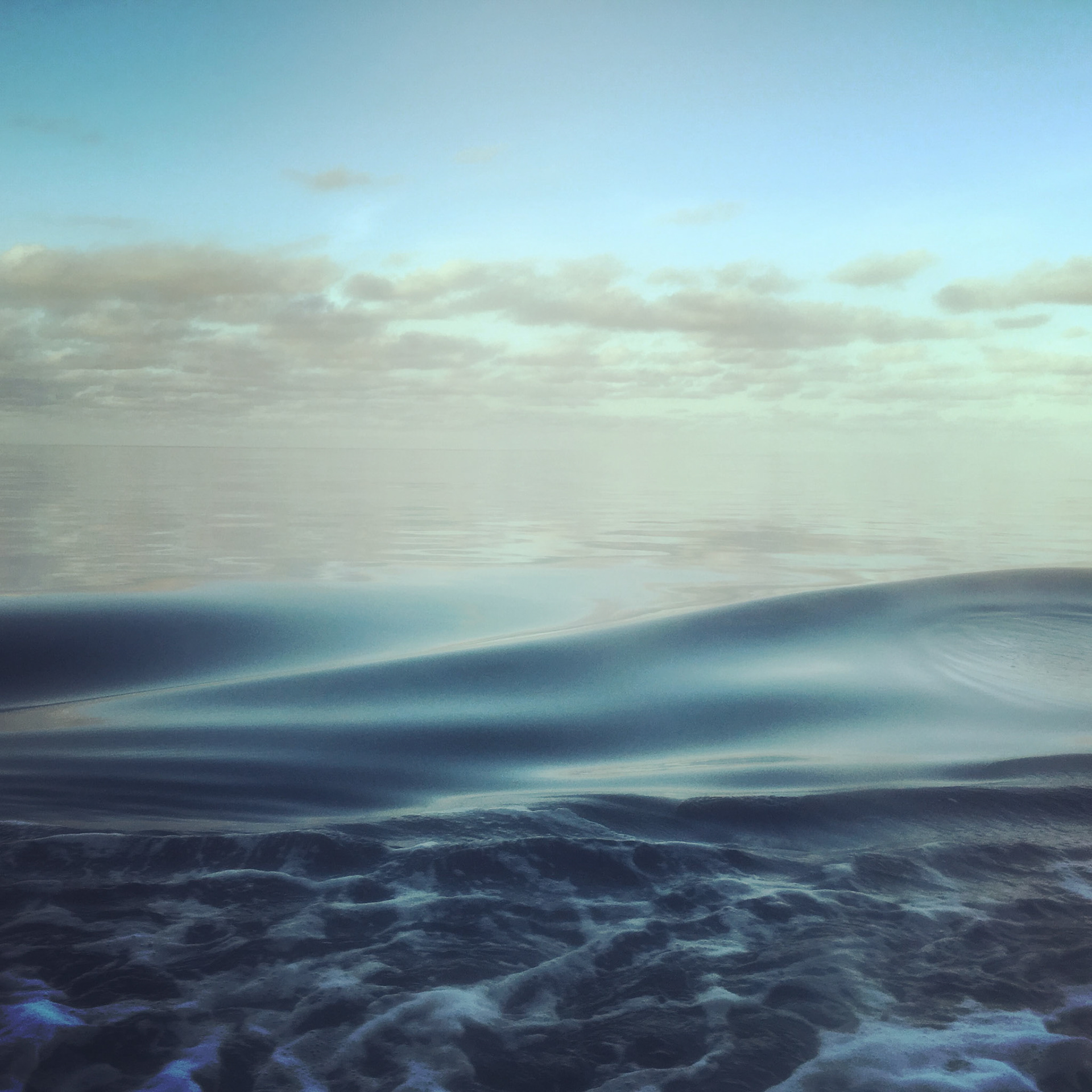

Like his nonfiction, Ben's instrumental music addresses themes of landscape, place, and environment: he's performed live in 48 states and held artist residencies with institutions including Acadia National Park, White Mountain National Forest, the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology, and the Schmidt Ocean Institute. In A Space Filled with Moving, an essay he calls "unusually personal," he grapples with the idea of spending so much of his life in motion, juxtaposing his personal narrative with braided sets of anecdotes about birds, floods, earthquakes, and other illustrations of a physical world that is also on the move.

Ben's chapbook is also available as a free digital download on Literary North's website.

All landscape photography by Ben Cosgrove

Molly Papows: How did this project and your collaboration with Literary North come about?

Ben Cosgrove: A Space Filled with Moving is actually an essay I've been kicking around for years, about movement and change and how to find meaning and ballast in a world where nothing holds still—which as a traveling musician are things I think about a lot. It's pretty different from everything else I've written: not only is it longer and much more personal, but it's also very fragmented and has this weird structure that gradually draws a bunch of different, unrelated strands together to illustrate something broader and more abstract. I had it on a back burner for years: I'd open it again and again, adding and subtracting whole threads as I tried to figure out whatever it was that was at the core of it. (In an oddly satisfying way, because I had this shape-shifting thing on my desktop for so long, growing and shrinking as I messed with it over the years, the process of the essay's development ended up aligning shockingly well with its own subject matter!)

Anyway, I started it back in 2016, when I was starting to write an album called Salt about very similar themes and was trying to clarify my own thinking about them. I didn't really know where I was going with the essay, but there wasn't ever really any intended audience: I was just trying to work something out for myself, I think, and it felt useful to keep working it over and over, even long after I'd finished the record. When Literary North wrote to me earlier this year and asked if I had any unpublished essays that might be appropriate for their Little Dipper series, I mentioned a few, but they were particularly into this one. At that point it was enormously long and unwieldy and on something like its thirtieth draft, but Rebecca and Shari were really interested in pursuing it, and did an amazing job of identifying the most important elements and mightily helping me distill it down to those. They're some of the best editors I've ever worked with, and I can't thank them enough for their help working this thing into the shape it needed to be. It feels fantastic to finally have it out in the world.

Photo by Matt Cosby

Molly: You have a keen eye for capturing moments that illustrate the give-and-take between a landscape and the community that inhabits it, and they’re often grounded in incredibly lovely, precise details. Like the man who conducts a growing cloud of seagulls through the air as he gestures with a garbage bag full of bread; it’s an absurd image, but it’s also beautiful to imagine the distinction between man, bird, and sky dissolving as you watch from your perch on a bluff. Do you often refer back to your daily journal as you write, or do those images tend to percolate in the back of your mind?

Ben: Thanks for mentioning that scene! It's one of my favorites. I don't actually refer back to my daybook (that's the sort of bullet-point journal I refer to in the essay, which just contains the raw facts of each day: "woke up here, drove here, played here, saw this person, slept here," etc.) that often, but in addition to that notebook, I have another sprawling document on my laptop into which I just dump anecdotes as they happen. I generally have a terrible memory for things that have happened to me, and I don't have a natural ability to convert my experiences into stories, so I started doing this six or seven years ago, to try and train myself to be better about applying narrative (and maybe, by extension, some degree of order or control) to my own life. And I open that thing all the time to mine it for stories that I might try to tell onstage, or work into an essay, or use as the jumping-off point for a new piece of music. That seagull scene is from there, for instance. But its primary function is to use narrative to apply order to chaos and meaning to events, all of which hopefully leaves me with a clearer understanding of my own experience and better equipped to make stuff from it.

Photo by Sofar Boston

Molly: I grew up in a coastal community defined by its relationship to the Atlantic Ocean, and I remember feeling an unexpected rush of claustrophobia when I first moved to Ohio for school. The rigidity of land-edged horizon lines in every direction was overwhelming, and it was something I had never considered until there was suddenly the absence of an ocean or even its orienting scent.

How much does your identity as a New Englander inform the way you experience new landscapes?

Ben: Probably in more ways than I'm aware of, but I guess I mostly have noticed it as it relates to topography. And your story resonates really strongly with me! I do have an old song about driving across Kansas that's a little like the experience you describe here—the idea behind that song, which is called "Abilene," is that it's supposed to illustrate the kind of panicky disorientation I felt the first time I drove across the Plains: how I couldn't tell where I was in relation to anything else, how fast I was going, or how far away these objects on the horizon were. So it's intended to sound big and broad but also a little unnervingly frenetic. And I think that landscape elicited that reaction from me because I grew up in central New England and I'm used to not being able to see very far, or to not being able to unconsciously orient myself in space by triangulating between landmarks. I'm pretty sure that no matter how far away I go, or how often I travel, my fundamental programming will always have been done by spending my formative years finding my way around this region; I think I remain pretty tightly calibrated to the way its spaces and systems work.

I don't know if you remember this, but at some speech during the 2012 campaign Mitt Romney made some offhanded remark to a crowd that was something like, "it's nice to be back here in Michigan; the trees here are all the right height." And everyone mocked him mercilessly, because of course it was such an utterly bizarre comment to make, but I actually found it to be one of the only relatable things Mitt Romney has ever said. For me, New England—and specifically north-central New England—is this visual-environmental benchmark by which I unconsciously measure every other setting in which I ever find myself. Its trees are the right height.

I also wondered about this a little bit when I was writing this essay, and back when I was composing the music on Salt, most of which is about places around here. I think New Englanders can't help but have a pretty complex relationship to change: on one hand we have a long and well-documented cultural tradition of being outraged by it whenever it happens (Maine and Vermont were the only states to vote against FDR), but on the other hand, we're also pretty well-attuned to cycles. For instance, we're famous for shrugging off things like miserable winters because we have this built-in understanding of how seasons are brief and impermanent and summer will come around again. "If you don't like the weather, wait five minutes"—that kind of thing. It could have to do with the compact size of the region, too: that one could be in places as wildly different as the Maine coast, the Pioneer Valley, the White Mountains, and downtown Boston, all within a couple of hours of each other, can leave us with an appreciation for the smallness and preciousness of all these component landscapes. We're never without an awareness of how so many very different environments are always so close by, and we’re used to watching one place change into another.

Molly: As she reflects on a lifetime spent exploring her beloved Cairngorms at the end of The Living Mountain, Nan Shepherd writes: "Knowing another is endless. And I have discovered that man's experience of them enlarges rock, flower and bird. The thing to be known grows with the knowing." I think about this passage all the time, and how it applies to people, paintings, books, and places. Does that feel true for you as you cross the same parts of the country in different seasons and at different times in your life?

Ben: Hm! That's interesting. And a really lovely line—it reminds me a little of the idea that people can only perceive things like, say, the color blue once their language has a word for it. My college girlfriend actually used to have a quote on her desk by John Stuart Mill, which said, in somewhat wordier form, something like, "a cultivated mind... finds sources of inexhaustible interest in all that surrounds it." Basically, that if you can maintain a natural curiosity, the world will be unendingly open and engaging to you, a bottomless rabbithole of things to wonder about. I've sort of employed that philosophy as a means of feeling at home even as I travel around so far and so often; to be honest, it's probably a big reason I started to write nonfiction, or to write music about nonmusical subjects I'd have to research and think hard about.

The more you can uncover about the world, the more familiar it becomes, but also the more confusing and fascinating. That is, the more you know, the more you find there is to know. I had an amazing writing teacher once who wrote magazine pieces on a crazy variety of different subjects, from climate change to basketball to air-traffic controllers, and he warned me once, "the thing about being a generalist is that if you're doing it right, you will always be the dumbest person in the room." That holds a weird appeal for me, and it’s part of why I keep flinging myself into new projects that may not logically proceed from my previous one. (For instance, I'm just coming off a year I spent playing with a rock band, and I spent the year before that writing music about a hiking trail.) I think I spend a lot of time trying to keep myself in situations that provide a kind of productive discomfort, where I have to really be actively scrambling to understand something; it's in the moments when I'm complacent or locked in a routine that I start to feel unhappy or adrift.

Photo by Rooted in Light Photography

Molly: You write about shifting borders, rushing water, and uncertain ground: towns can disappear only to reemerge on the opposite side of a river, mountains can become islands, and the Wreckhouse winds of Newfoundland can casually sweep trucks from the road. You've spent a decade now observing and processing the impermanence of landscapes across the continent. Has that changed the way you situate yourself within familiar and well-loved spaces when you’re home?

Ben: It always does, for sure! The more I've explored, the more context I've come up with for the landscapes I've known my whole life. In many cases, it's left me with a deeper appreciation for their specialness (there's still nowhere else like Mount Monadnock or the region around it), but in just as many others, it's taught me how so many of the things I might have thought of as fundamentally New Englandy are in fact part of broader phenomena that are expressed across much wider landscapes. I feel like I'm constantly stumbling upon new ways in which the places I love are simultaneously utterly unique and intricately connected to everywhere else.

Molly: You describe the way recurring landmarks orient your movement across the country “like common tones in a harmonic progression.” I feel that way about the books I revisit through the years. Who do you find yourself reading and drawing inspiration from as you travel? Who has had the strongest influence on your writing?

Ben: Oh! Jeez, I don’t know; it always changes. I definitely draw a lot of inspiration from Rebecca Solnit and John McPhee, each of whom can write about place—very differently—with incredible clarity and insight. I also reread Moby-Dick every year (this used to be a weird secret of mine, but I've since met at least one other person who also does it, so I feel I can come clean). I've also just got rows of books stacked in the passenger seat of my car, and they usually contain the things I'm most excited about at the moment. Right now Jane Kenyon is in there, and John Ashbery, and Robert Lowell, because I've been on a poetry kick, but I've also got the new book by Barry Lopez, which blew my socks off. And this brilliant little thing called "The Summer Book" by Tove Jansson that my friend recently lent to me. And Jia Tolentino's essay book from last summer, which contains such clear and compelling writing about so many of the most confusing and chaotic elements of modern life, and is just screamingly good.

I feel like instead of answering your question I'm just ramblingly listing books that I have recently liked, but I don't think I mark time and place with books the same way I do with the music I listen to. Hearing certain songs will emotionally rocket me directly to, you know, the late spring of 2014 or whatever, but for some reason it's different with books in that I don't exactly geotag and date my experience of reading them the same way I tend to do with music. Which is weird! Thank you for making me suddenly realize this strange thing about myself.

Molly: You write about a period in your life of nearly constant travel—of trying to be everywhere in an effort to hold onto everyone and everything—and while your career is certainly unique, I think that feeling will resonate with a lot of people. Was it disorienting at first to allow yourself a slower pace and moments of stillness?

Ben: I guess one thing I've found is that I'm not very good at being still, and a major reason for writing the essay was to figure out whether that was fundamentally a bad thing or not—I'm very much in love with the process of moving around and in writing this, I wanted to see if I was just being irresponsible, short-sighted, or self-indulgent by building a life around that, or if it was actually possible to square all that travel with a coherent philosophy and worldview. It really compelled me to think about why I feel so fulfilled while traveling around and cramped when stationary, and whether those feelings could be explained by unpacking a few of these other cases in which movement and change can be seen to be more dependable elements of the world than anything else we might try to lean on or put our faith in.

And obviously, I do still run around like a maniac. I don't think that's changed, but what has is that I've come to understand a lot more about why this appeals to me so much, and about what I'm gaining and losing by conducting my life and career this way. Another big shift from my days of just deliriously sprinting around the country all the time is that I've tried, over the last several years, to consciously try and be more of a meaningful part of the places I move through, rather than some visiting observer: to be a good friend, to be a valuable part of a community, to sustain relationships. I'm still usually in a different place every night or two, but now, at least for much of the time, that's happening within six or seven states, not 48; I'm not just tearing between Minnesota and Wyoming to play at dive bars all the time.

I do feel that I'm able to be the best possible version of myself by living and working this way, and I've been lucky in that I've managed to remain surrounded by a pretty amazing constellation of close friends and relatives; those relationships keep me from ever feeling isolated, alienated, stagnant, or alone. At the end of the day, I think all anyone really wants is to know how to be a good person despite the unique constraints of their own life, and my particular challenge has been working out how to do that while moving around enough to be making my living as a performer.

Molly: Your work illustrates the shape our emotions can give to a landscape and the form a landscape can give to our state of mind. Those same physical landscapes are also being altered by climate change, sometimes slowly and sometimes with catastrophic speed. Do you consider yourself an activist, and do you see your music and nonfiction writing functioning similarly in that sense?

Ben: This is a great question! I'm definitely not an activist—I actually think that art and activism, while obviously each is important and necessary, have fundamentally different functions and goals. With activism, you have a particular set of desired outcomes: you want to persuade people of something and compel them to a specific set of actions. The best, most effective activism is very straightforward, prescriptive, and unambiguous... and these are qualities that tend to make for some pretty miserably bad art. I feel that art should elicit a variety of interpretations and leave people with more questions than they came into it with, and an activist who had that effect wouldn't be great at his or her job. I think the two work best in combination with each other.

What I always hope for from my audience, rather than any specific reaction, is that my work will raise questions in people's minds about how they perceive and engage with the world around them, and that those individual lines of thought that result might potentially lead them to a greater sense of orientation, or wonderment, or curiosity, or awareness. One of my most deeply-held personal beliefs is that the vast majority of our environmental and societal problems—from gentrification to climate change—tend to come less from cruelty or malevolence (though there's plenty of that these days) than from a failure to dwell thoughtfully on questions about how we relate to our local and global environments, or what all these places, all these landscapes, might mean to us. Climate change has resulted in part from a longstanding cultural tendency to think of the physical world in terms of quantities and commodities rather than a set of interlocking systems and places with meaning and dignity and inherent importance. I think it often just doesn't occur to most people to think about the landscapes they inhabit or how they engage with them.

My hope—and I guess this is the closest I get to a mission statement—is that by playing all this music about landscape and telling all these stories, I might have some small impact by inspiring people to wonder what their own thoughts might be: what their own song about Kansas might sound like, or what feelings a particular scene elicits from them. If I can get people to care a little more about the landscapes they'd otherwise ignore or overlook, just by inspiring them to wonder about how they truly feel about them, it might incline them toward more thoughtful stewardship and I will feel like I've done something useful. But that can only go so far, of course. We really need activists, too.

November 2019

Photo by Daniel Lombardi

Ben Cosgrove is a traveling composer-performer whose music explores themes of landscape, place, and environment in North America. Ben has performed his "electric and exhilarating" instrumental music in every U.S. state except Delaware and Hawaii, and held artist residencies and fellowships with institutions including the National Park Service, the National Forest Service, Harvard University, Middlebury College, the Schmidt Ocean Institute, and the Sitka Center for Art & Ecology. His recent album "Salt," which compares feelings of ungroundedness and confusion to landscapes of flux and ambiguity, was described by Seven Days as a "majestic entry into the composer's catalog... replete with near-imperceptible embellishments and forward-thinking concepts." His nonfiction has appeared in Orion, Taproot, Northern Woodlands, Maine Farms, and other publications. For more about Ben's work, please visit his website at bencosgrove.com.

Molly Papows is an art historian based in Lebanon, NH. She has an MA in the History of Art and Architecture from Boston University and ten years of experience working in encyclopedic fine art museums. She's also interested in the many ways an artist can tell a story across disciplines—from fiction and nonfiction to poetry, landscape architecture, and music.