Vanessa Compton lives a semi-nomadic existence. She spends part of each year working in her studio in the hills above Caspian Lake and co-directing Miller’s Thumb Gallery in Greensboro, Vermont. When winter comes she heads to the American Southwest, where she lives in a 65-year-old camper and serves as a guide at Hueco Tanks State Park. After closing up the gallery one evening in September, Vanessa took a break to discuss two of her greatest passions in life—climbing and collage—and to share her current studio playlist.

Do you have a specific plan in mind when you start working on a collage? Or does the piece emerge organically over time?

When I start a piece, I know the general layout—the architecture, the scaffolding, the horizon. I’ll usually have a couple big images that I’ve been saving, and I know where they are going to be placed. If I’m doing one of my planet pieces, then I’m obviously going to have a circular orb to work from. But the specifics of what and who goes where, that just happens in the process.

Where do you find the images that you use in your collages?

They’re always found images, straight from magazines or books—I never use the internet for finding images. People know that I’m a collage artist, so they donate magazines. I have to be more discerning now because I have too many that I’ll never go through. I don’t want Martha Stewart Living—the more obscure and small-edition the magazine, the better.

Do you cut out all the images before starting a new piece?

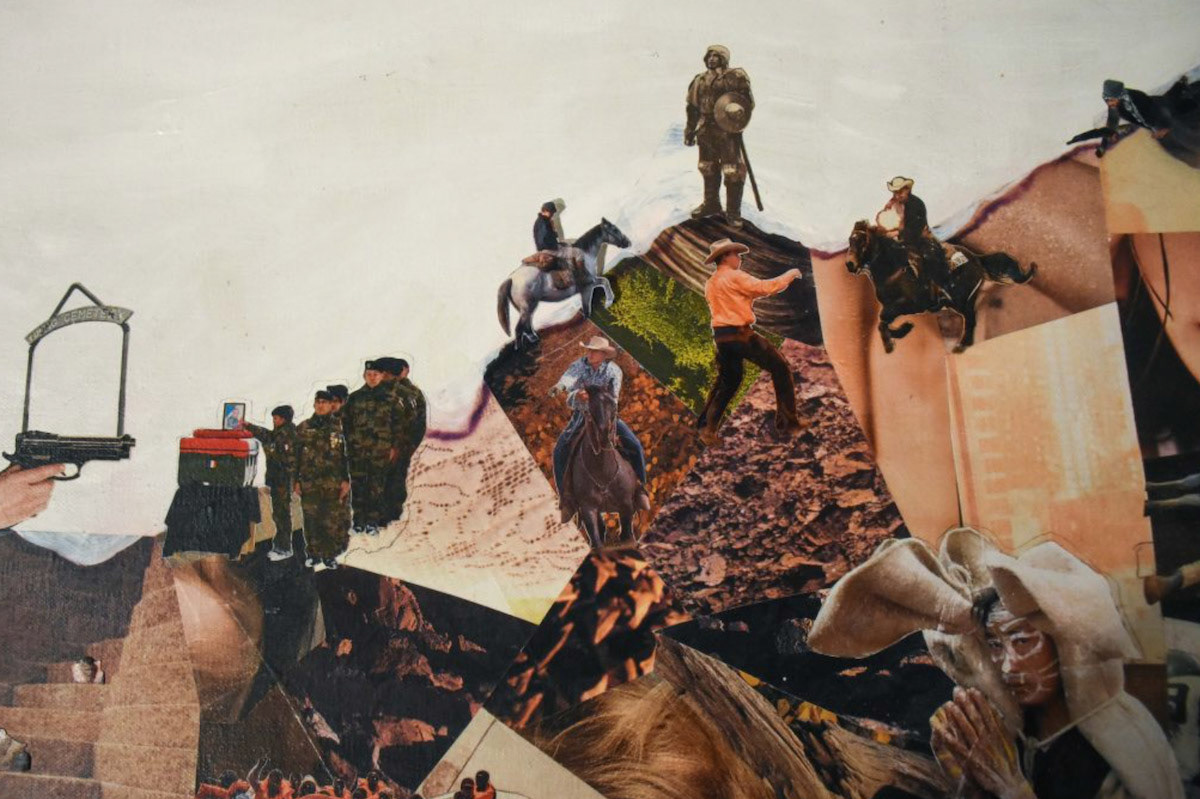

Whenever I find something that speaks to me, I immediately cut it out. I have everything organized into these little baggies. I might pick up ten magazines and just cut out colors all day. It’s like doing mosaic. And I organize everything by subject matter: furniture, surfing, the feminine, the masculine, skiing, eyes, hands, children, animals, youth, cowboys and Indians, war. I try to use images in a way that challenges and breaks down stereotypes, and I like to have as many cultures represented as I possibly can. By having a proliferation of cultures, I can really elevate the beauty of our differences—our ceremonies, religions, colors, experiences, backgrounds. I want a recognition of our similarities and a celebration of our differences, which is what a lot of my pieces are about.

Did you grow up in an artistic household?

Both of my grandmothers are artists, and one worked often in collage. My dad is a professional musician, and my mom got her degree in ceramics, so visual art and music was everywhere. I was born in Woodstock, New York, but we moved around a lot. Every summer we’d come up here to Greensboro, and it’s the one place that has ever felt like home. When I think of the visual landscape of childhood, it’s here: the view, the fields, the big windows and the light.

Did your mom influence your decision to study ceramic sculpture in college?

I am grateful to both my mom and dad for always supporting my artistic journey and for making me feel like it was vitally important to pursue what felt right and to be true to myself. In high school I did a lot of sculpture and ceramics, and I loved working with my hands, but I also did music and theater. After graduation I did a year at a theater conservatory. I thought I wanted to be an actor, but after a year I just got depressed being in a black box theater day in and day out. I would come back to Vermont almost every weekend, and I missed the natural world. I took a year off and did a NOLS semester in Arizona—it’s like Outward Bound. It was my first time going out west and I slept outside under the stars for 90 days straight. Being out in the wilderness, having to go long periods without a mirror or shower or access to indoor plumbing—it helped build up a lot of self-confidence. And I also fell in love with climbing. All throughout high school, I was an arts geek. I was never a jock, and I’m not a competitive person. I loved that climbing allowed me to push myself—my body, my strength, my mind.

What was your first experience with climbing like?

We went to Cochise Stronghold in Arizona. It’s not necessarily hard climbing there, but they're all multi-pitch routes, meaning many, many rope lengths and generally you're out on the rock from sunrise to sundown. I loved the feeling of pushing to do something that seemed so dangerous, like life or death, but that in actuality was measured and quite safe. As an artist, I never thought that I could do anything physically challenging. In sixth grade they’d have those tests to see how many pull-ups you could do, and I could never do any. I ended up moving back to Vermont and worked at a climbing gym in Quechee. I remember I had only been climbing a few months before I thought to try doing a pull-up, and I could immediately do five. I couldn’t believe it! Shortly after that, I ended up at CU Boulder to get a Bachelor of Fine Arts and also worked at a climbing gym there. Boulder is basically where all the professional climbers live at some point in their lives.

Did you stay out west after college?

I lived in Colorado for nine years and worked as an arts educator at a private school. It was part-time, so I had side gigs, like working as an assistant to a tabla musician. Then, on my 27th birthday, which was on the 27th of October, we had a staff meeting at the school. We were sitting in a circle, under fluorescent lighting, holding a talking stick, and I was thinking to myself, what the hell am I doing? I always thought that I was going to be doing something amazing when I turned 27. I was teaching art to young people, which was rewarding, and I loved my students, but found that I wasn’t actually doing art like I wanted to. It felt like I was living someone else’s life. I ended up not renewing my contract at the school, made some big personal changes, and moved out of Boulder. Later I found out that it was my Saturn Rising, which is a time in life of great transformation. I also decided then that I wanted to try splitting part of my time in Vermont and part of my time out west each year.

How do you make that work?

It’s not easy. There’s a lot of financial insecurity, and also family expectations: Are you going to get married? Are you going to have kids? But things have fallen into place and I have zero regrets. My partner and I have a van and ’52 camper and travel throughout the American Southwest every winter. I spend the majority of that time climbing and also working as a guide at Hueco Tanks State Park, about 35 minutes outside El Paso. It’s one of the top three sites in the world for bouldering and also well known for its large collection of amazing pictographs.

In terms of culture and landscape, you’re jumping between two of this country's biggest extremes.

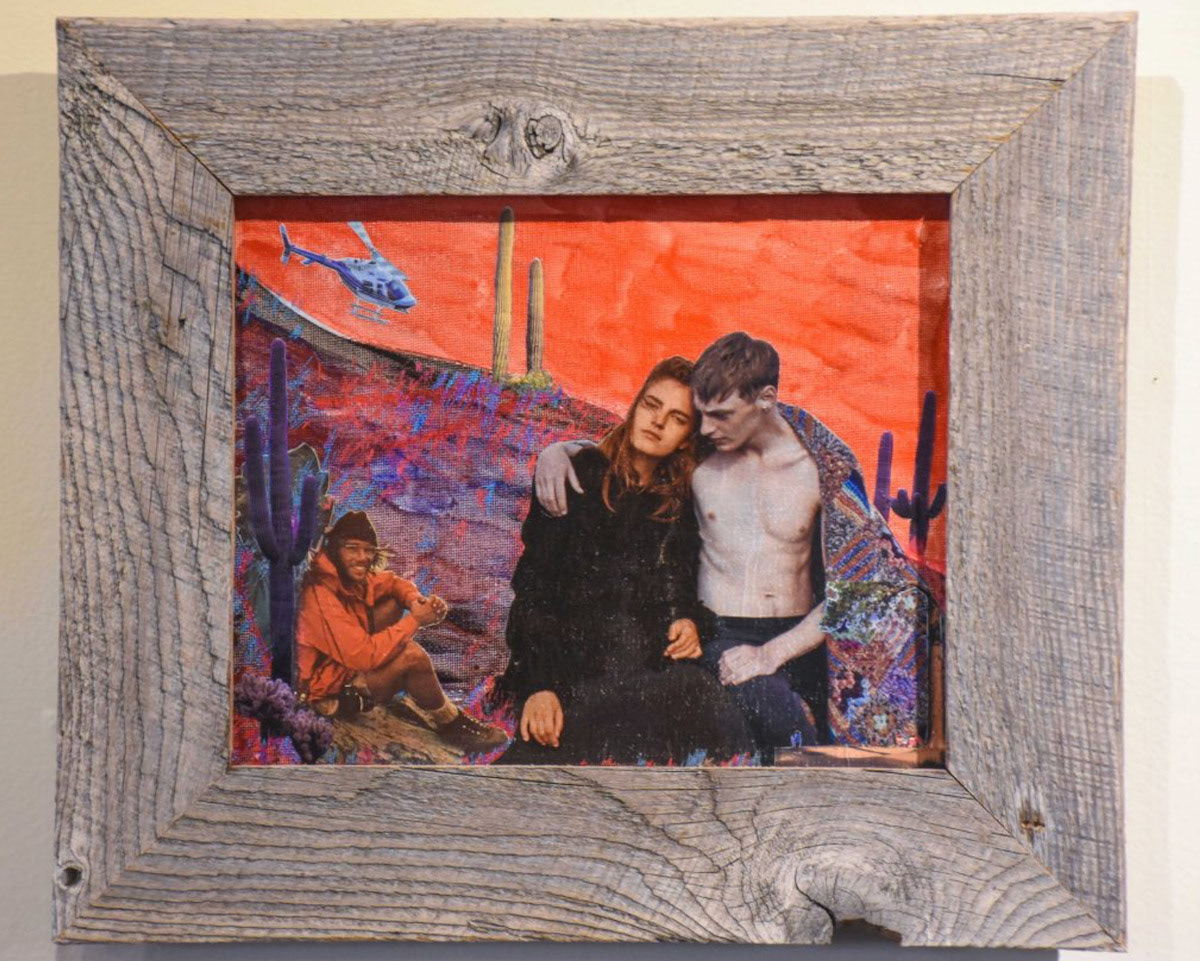

It’s interesting to be near both borders. Here we welcome Quebecois visitors, while in Texas there’s border patrol everywhere. You see them storming past on ATVs and in helicopters. Fort Bliss is also close by, and you can hear AK-47s and see bombs going off in the distance. It’s a really charged place.

It’s interesting to be near both borders. Here we welcome Quebecois visitors, while in Texas there’s border patrol everywhere. You see them storming past on ATVs and in helicopters. Fort Bliss is also close by, and you can hear AK-47s and see bombs going off in the distance. It’s a really charged place.

How much does your immediate environment impact your work?

To be creative, I just need time and discipline. I’ve found that I need to be basically disconnected, because I’m easily distracted. I don’t struggle with writer’s block—I have unending ideas—I just need to push myself more to make it happen. That’s somewhat challenging now because of my job co-directing the gallery. It’s just a two-woman operation, and we’re open every day. I’m an introvert, and after talking to people all day I need to recharge. Sometimes my artistic process isn’t as productive as I’d like it to be, so I try to do a residency every year or two. I’m always applying for residencies—they’re very competitive. Being an artist has been great for learning about ‘no’s, because you often experience rejection.

Tell me about your most recent residency:

Last November I did one at the Hubbell Trading Post on the Navajo Nation in Arizona. It was through the National Park Service—they have a program to give free accommodations to artists in exchange for donating a piece and giving a public talk. I lived in a hogan, which is a traditional Navajo dwelling, for two weeks. The piece I donated was called Kinaalda—it’s the name of a Navajo ceremony that, over the course of four days, marks the transition of a girl to womanhood and celebrates the ties that bind the community together. During this time a girl performs different activities, like preparing a large corn meal cake that cooks for several days and is then shared by the family and community. In the original collage I actually used corn stalks from the Hubbell Trading Post. I was coming in as a foreigner, so I incorporated other coming-of-age ceremonies from around the world into the piece. I also had visitors stop by before everything was glued down, and I would ask women who had experienced Kinaalda for their thoughts and recommendations.

In your artist statement you note an interest in the idea of luxation, or disjointedness, and in surreal landscapes that blur time and space. Can you talk about how you play with these themes in your work?

Collage allows me to mix all these disparate parts into one piece. Unlike representational painting, where I’d need the technical skills to paint everything exactly as it looks, I can just put images together that may have never been side-by-side before and create a kaleidoscope effect. I feel like it’s the human condition to get so caught up in this present moment in time, and it’s an artist’s responsibility to pull back the veil on our experience. We should reflect on what has worked in the past and what hasn’t, and not be so easily seduced by what is pleasurable with new technologies. I don’t even have a smart phone, though it has probably been a disservice to me as an artist. These devices are wonderful because you can share your work and see what other people are doing around the world for free. And sure, it feels fantastic to get tons of likes on your Instagram posts, but we should have more questions about this technology’s place in our lives and how it affects us emotionally and physically.

He was speaking before the age of social media, but David Foster Wallace described that kind of external validation and fame as a “greasy thrill”—it feels really good, but in an entirely unwholesome way.

It is pleasurable, but it’s also an addiction. These things are very new. I wish there would be more pauses in life, when everyone just took a break to evaluate what has been helpful and what hasn’t, and to question the systems that are in place.

It is pleasurable, but it’s also an addiction. These things are very new. I wish there would be more pauses in life, when everyone just took a break to evaluate what has been helpful and what hasn’t, and to question the systems that are in place.

Who purchases your work?

I participate in regional and national exhibitions and also open my studio up to the public several times a year. The buyers have mostly been people who live in urban settings—Montreal, New York, L.A., San Francisco. I was super stoked recently when the archivist at the National Gallery of Canada ended up getting my biggest piece ever.

Do you make your own frames?

I struggled for a long time to find frames that wouldn’t compete with the collages, which can be very busy, visually. I started using barn board—there are old barns falling apart everywhere in Vermont. I really like if there are nails and little imperfections, so you can see the life that it’s lived. It has the maker’s hand on it, which I love. And the wood is steadfast. It’s a contrast with paper, which is so delicate and fleeting, and can be easily torn. For me, the wooden frame feels like the period to the sentence of a piece. It’s also nice because the frames aren’t fragile, so if you ding them up a little bit when moving the art, that’s okay.

Where does the medium of collage fit within the world of contemporary fine arts?

Collage is starting to become the new hot shit. It has been an esteemed art form during different periods, but many people think it’s done really quickly. If you have a glue stick and some magazines, you can do it, which is awesome. Personally, I like doing collage that takes forever. Sourcing the images, cutting them all out, putting them together—that takes so much time and patience and precision and meticulousness. Doing that really satisfies me. When I view other collagists’ work, I immediately look at the skill of how they’re cutting it.

What tools do you use for cutting images and putting everything together?

Initially, I use big scissors to cut out big images from magazines. Then I just use these Fiskers. The blade is a couple inches long, but I really only use the last quarter. You can bring scissors up to three inches long on flights, so I’ll be the crazy woman on the plane with a bunch of plastic bags, cutting out images from the magazines in the back of the seat. Some images take an hour to cut out, like if it’s feathers and you have to go in and out of every detail.

How long does it take to finish a single collage?

Pieces can literally take months to complete. In addition to the cutting, the layers also take time. When I start a piece, I just do the landscape. That’s where I either do some acrylic or put all the color pieces of paper together like a puzzle. I don’t really overlap them. Maybe no one notices, but I want all the lines to match up perfectly. I’ll soften the paper with acrylic or oil. Then I’ll add the details, like the people or the creatures that live there. Then I do a fourth layer of more paint and details, and then the fifth layer is the oil-based archival varnish, which helps reduce UV fading. I like bringing collage up to a level where it’s very meticulous and takes great patience. It’s not going to be easily reproduced. It all takes goddamn forever, and that’s why I like it!

Vanessa's Studio Playlist

Fallen Angel• Robbie Robertson

License to Kill• Bob Dylan

Poor Black Mattie• R.L. Burnside

Skinwalker• Robbie Robertson

Grotto Farm• Compton & Batteau

Ambulance Blues• Neil Young

Broken Arrow• Robbie Robertson

Tajabone• Ismael Lo

For the Rest of Your Life• Hope Sandoval & the Warm Inventions

The Magdalene Laundries• Joni Mitchell

Golden Pilgrim• The Skygreen Leopards

Hummingbird• B.B. King

Myrkur• Sigur Ros

I'm to Blame• Boardwalk

Girl Out West• Speck Mountain

That Teenage Feeling• Neko Case

Broken Arrow• Robbie Robertson

I Believe in You• Talk Talk

View more of Vanessa’s work on her website, Facebook, and Instagram(@krinshawstudios). Miller’s Thumb Gallery is open May 15-October 13; learn more about the gallery on the web, Facebook, and Instagram(@millersthumbgallery).

James Napoli is the founder of Junction Magazine. James has since moved to Minnesota and all content is managed by a collective of artists. Read more about them here.