Afterlife

In the mid-1800s, two gravestones were placed near the base of a young tree in the Old Dartmouth College cemetery. Slowly — imperceptibly slowly — over more than a hundred and fifty years, the tree grew fatter and fatter. It’s begun to swallow the stones and will likely continue to do so. When we die, life goes on without us. - Colleen Goodhue

Photo by Colleen Goodhue

Daniel L. Cady - Vermont’s obscure poet at the turn of the century

At the top of Strawberry Hill in Brownsville sits a mausoleum. The famous or infamous — depending on whose tale you hear about him — Vermont poet and lawyer Daniel L. Cady rests in a large memorial surrounded by a short fence and taller weeds. At one time it would have been a spectacular view for the afterlife with Ascutney looming over the gravesite and Cady looming over West Windsor. Though a large burial place, it is a small shack-looking building from the back, complete with a boarded up little window. As one comes around to the front, you see the granite columns and steps. And then one notices that the entire building is granite. According to the West Windsor Historical Society the mausoleum cost around $38,000 in 1934 (during the Great Depression) when Cady died, about $700,000 today. Like the inflation of the dollar, it is reported that Cady may have had a bit of an inflated sense of self. The memorial took a few years to plan and build, and of the location, Cady supposedly wrote in a letter in 1931, “People will have to look up to me whether they want to or not.” - Isaac Lorton

Photo by Isaac Lorton

Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Often considered the greatest American sculptor of the 19th century, Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ ashes are entombed in a Roman-esque sacrificial altar in an open field, backed up against trees, along a ravine. Saint-Gaudens is known for his Civil War memorial sculptures and founding the artists’ haven the “Cornish Colony” in New Hampshire. The compound is now a national historic site. The informational plaque at the “Temple” where Saint-Gaudens is buried reads “Created in 1905 as a stage set for a classical-style pageant ‘A Masque of Ours; The Gods; The Gods and the Golden Bowl.’” The original was done in plaster, but was redone in Vermont marble in 1914. Saint-Gaudens died in 1907. An inscription from the Book of Revelations on the back of the altar reads, “Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord… that they may rest from their labors; for their works do follow them.” - Isaac Lorton

Photo by Isaac Lorton

Photo by Isaac Lorton

Tombstones on the VAST trail

On a hot and humid early July afternoon, I ventured out on one of Vermont's unmaintained class IV roads at the end of Birch Tree Farm. I stumbled upon something quite eerie, yet lovely, tucked away within the myriad trails of the VAST system. The cemetery is now home to a pleasant couple, perhaps forgotten in memory, but not in time. - Scott Achs

Photo by Scott Achs

Photo by Scott Achs

Photo by Scott Achs

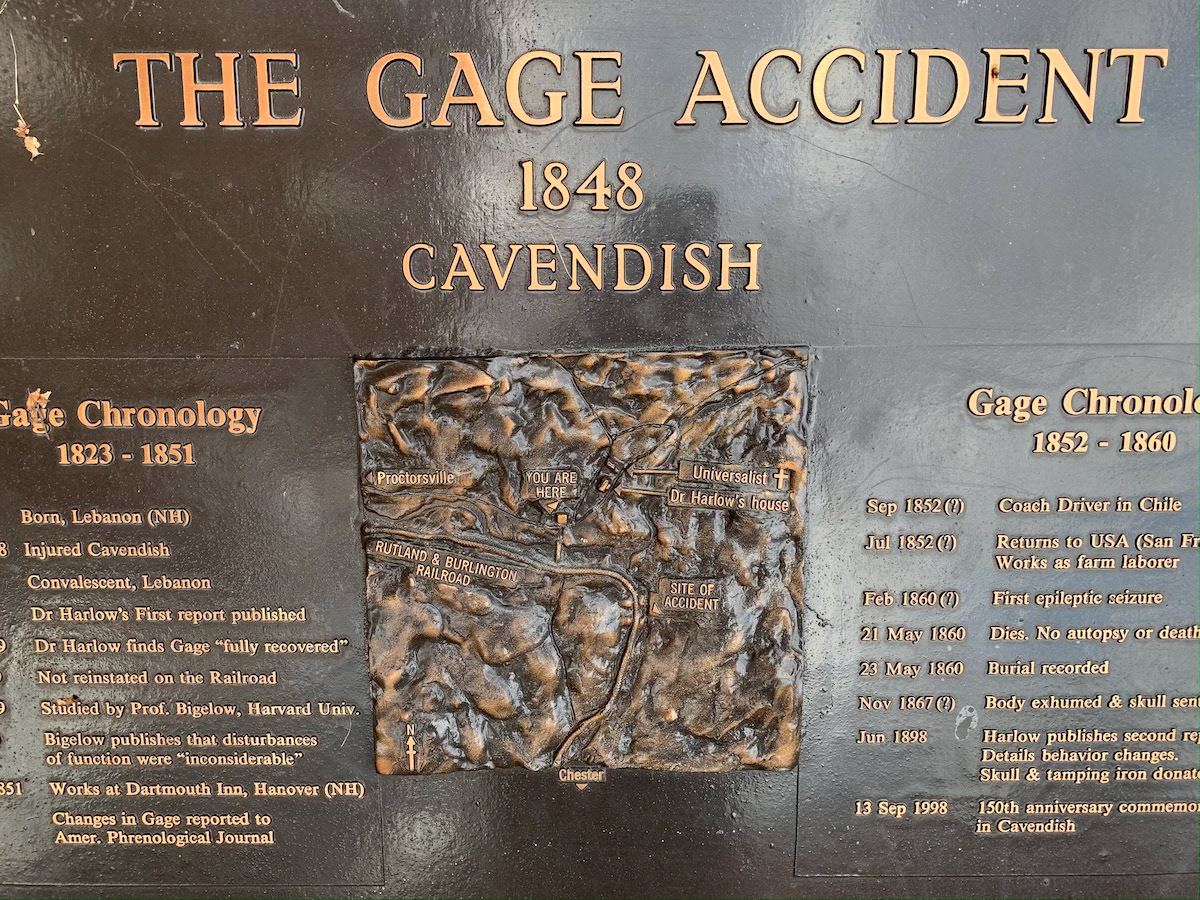

The curious case of Phineas Gage

Not so much a death memorial as a near-death memorial, at the intersection of Main and High Streets in Cavendish, Vermont, you’ll find a stone and plaque marking the famous nearby accident wherein Phineas Gage, a railroad construction foreman, had a tamping iron go straight through his head. Remarkably, Gage didn’t die, but went on to live nearly 12 more years, though those close to him noted a marked shift in his personality. Gage’s family donated his skull and the tamping iron to local doctor John Harlow who helped Gage recover. They’re now on view at the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard. The marker in town was set up by the Cavendish Chamber of Commerce and Cavendish Historical Society in 1998 to mark the 150th Anniversary of the accident. The Historical Society hosts an annual walk and talk in September to commemorate it. - Taylor Long

Photo by Taylor Long

Photo by Taylor Long

Photo by Taylor Long

An opulent final resting place

At Laurel Glen Cemetery in the small village of Cuttingsville, Vermont, you’ll find the Laurel Glen Mausoleum (also known colloquially as the Cuttingsville Monument), which has the unforgettable sight of a life-sized sculpture of a man peering inside. Leather and tanning magnate John Porter Bowman had the mausoleum built after his two daughters and wife passed away, leaving him as the sole member of the family. Truly a labor of love, the Laurel Glen Mausoleum took 125 people one year to create from 750 tons of granite and 50 tons of marble, and cost an incredible $75,000 (in 1880). Bowman later built his summer and retirement home across the street, where he lived until he too passed and was reunited with his family in the mausoleum. In later years, stories arose claiming his house is haunted. Due to his supposed belief in reincarnation, Bowman left $50,000 for the upkeep of the house and monument, though the funds eventually depleted in the 1950s. - Taylor Long

Photo by Taylor Long

Photo by Taylor Long

Photo by Taylor Long

Photo by Taylor Long

October 2019