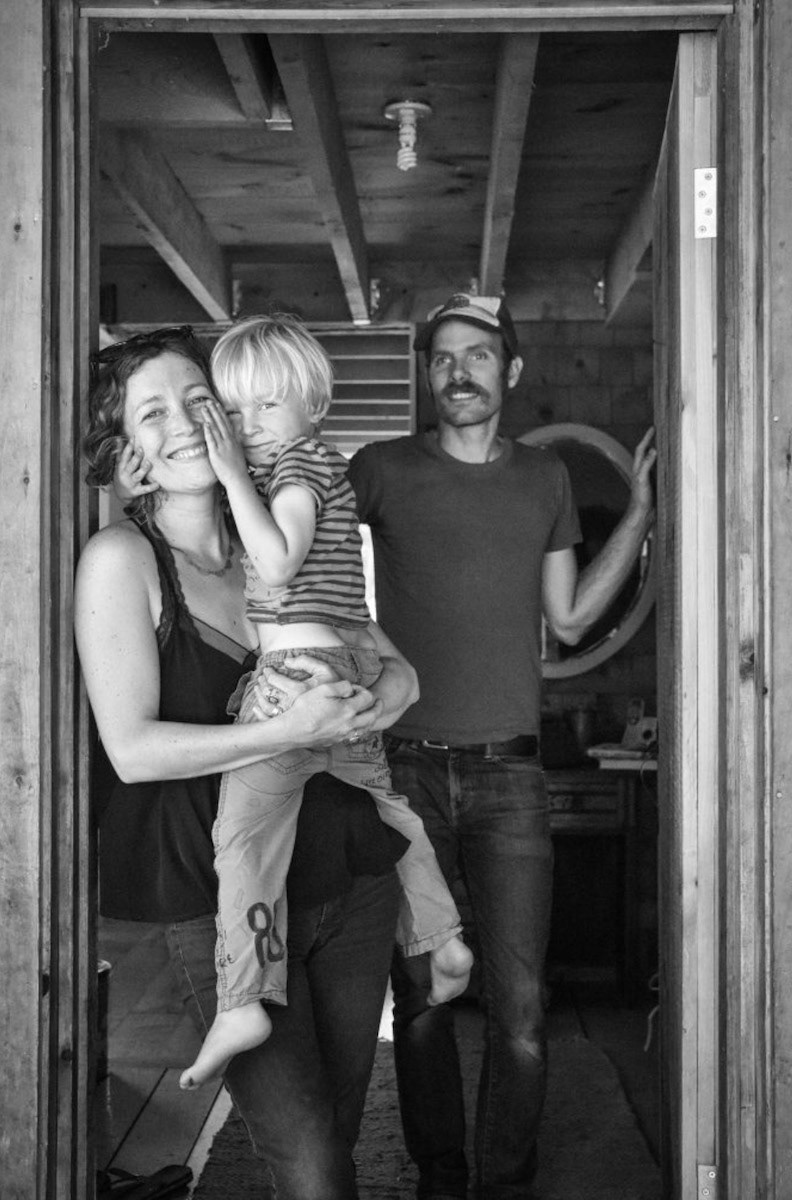

Windham County natives Robin MacArthur and Tyler Gibbons left Vermont to pursue creative endeavors in the city. After a few years in New York and Philadelphia the couple could no longer resist the pull of their rural roots, so they moved back home to build a cabin, raise a family, and cobble together careers in writing and music. This week they celebrate the publication of Robin’s first book, Half Wild, as well as the fourth—and possibly final—album from their indie-folk duo, Red Heart the Ticker.

Are you both originally from this area?

Robin: I grew up right here on this road. My grandparents actually moved here in the late ’40s when my grandfather got a job teaching science at Marlboro College. They were early homesteaders—Nearings Era back-to-the-landers. There were no other houses on the road at that time, just this abandoned farmhouse at the top of the hill. The floors had been eaten by porcupines, there were bullet holes in the front door, and it didn’t have running water or electricity. They bought it and fixed it up themselves, and they raised five kids here. They grew a lot of their own food and harvested their own firewood. Then my dad and his siblings continued that tradition in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Tyler: I grew up in Brattleboro…not as interesting a story as Robin’s.

Did you have much music in your home when you were growing up?

Robin: My grandmother, Margaret MacArthur, was a songcatcher here in Vermont. My dad and uncle and aunt would play with her, too. I grew up going to folk festivals, sometimes even sleeping right on the edge of the stage. There were always spontaneous house concerts happening at the farmhouse up the road.

How did your grandmother get into folk music?

Robin: She spent the first couple years of her life in Chicago, where she lived in a house with 20 family members. Her stepfather worked for the U.S. Forest Service, so they moved to Utah and then to Northern Arizona. My grandmother spent several years there living in a tent, listening to the cowboys outside who would sing around the fire every night. Then the family moved to Southern California. She had to ride the postal truck an hour each way to school every day with another kid who was Mexican-American, so she learned all these songs in Spanish. Then they moved to the Ozarks of Missouri and then to Kentucky—places with really rich musical cultures.

Did she start collecting songs here in Vermont?

Robin: She followed my grandfather to Vermont and, the way she told it to me, fell into a deep depression because she couldn’t find music here. She was lonely in the old farmhouse and needed to figure out the culture of this place, which she understood via music. There was church music, but that didn’t seem vibrant and alive to her. She started traveling around in the late ’50s with a reel-to-reel recorder and with her kids in the back of her jeep, and she would ask people, “Do you know anyone who plays music or remembers the old songs?” Now all of her recordings are at the Folklife Center in Middlebury, and there are clips from some of those recordings on our new album.

How did she end up putting out her own album on Folkways Records?

Robin: She played at a house concert in one of the neighboring towns, and Moses Asch from Folkways was there. He asked her to send him a few of her songs. She went home to record the music at her kitchen table, right up the road here, playing guitar and singing with the kids in the background. She thought she was just sending in a demo, but it came back to her as an album. She spent her life performing as a professional folk musician after that. I got to spend a lot of time with her, listening to her sing, and she was also just a really good friend of mine.

You both left small-town Vermont to attend college—Robin at Brown, Tyler at Harvard. What did you study?

Robin: I studied comparative religion and art and writing and literature—your classic liberal arts stew.

Tyler: I was an English literature major, and I lived in a place called the Dudley Co-op. Harvard owned it, but it was off-campus, the kind of place where the misfits and the seekers lived. It was, by far, my best education. I took some great classes, but living in that house with all those amazing, interesting people—that’s where I really went to college. And I would go off every weekend to play shows around New England with this old band of mine, so I always had one foot outside of everything that went at Harvard.

What did you do after college?

Robin: We moved to New York. I was working for documentary filmmakers and also writing, just on my own, and painting.

Tyler: My whole life I knew I wanted to be a musician, and I never imagined that I would stay in Vermont. I always had it in my head that I either needed to live in New York or L.A., or maybe Nashville. When we moved to New York I thought I would be a session bass guy, or even a touring bass player, and I did some of that. I also started film scoring back then.

But you ended up moving back to Vermont together?

Tyler: When you grow up here, this place haunts you a little bit. There’s the practical side, too. We wanted to live creative lifestyles, but New York was almost impossible after a certain point because the rent was so high. We were working full-time jobs to pay the rent, and then we were too exhausted to go practice.

Robin: Primarily, we could live here for free, and we built our house over time as we made money. We built this first cabin together in 2003. While we were living in New York, and later in Philadelphia, we would come back up here. It just had a little woodstove and funky gas stove at the time, but it was our Vermont hideaway. It reached a point where we just didn’t want to be anywhere else, so we added on to the cabin and made this our permanent home.

When did you start playing together as Red Heart the Ticker?

Robin: Ty was recording an album in New York, and I did some singing on it. Then I started writing more songs and recorded a little demo of my own. We started playing out together in West Philly and, in 2005, we recorded our first album, For the Wicked.

Tyler: We landed right in the middle of that West Philly scene. We went to a lot of shows in those big houses out there. I loved how the shows often, maybe even deliberately, didn’t have a theme. There could be three acts, and one would be a really loud punk band, one a freak folk thing, and one a country music thing.

You recently completed a CSA-style creative project where you put out a new song every month. How did that work out?

Tyler: That was called Songs in the Lunar Phase. The idea was that we would write and record a song every month. Then, on the day of the full moon, we would send it out to a few hundred subscribers who had paid us a little bit of money. It would show up right in their inbox. We didn’t put it up online—it was just a personal connection. It was a passion project—and it was a lot of work. Even though we pitched it as a way to share works-in-progress, there was a certain amount of pressure because we wanted the music to be decent. There were some hectic late nights, when the moon was almost full, and we were trying to revamp songs. I’d started doing film scoring as a career at that point, so this project was a way to create deadlines and insure that I kept writing songs.

Did the songs on your new album, Tigers of the New England Forest, come out of the Lunar Phase project?

Tyler: Yeah, quite a few of them did. We took a break for about a year, then went back to think about which songs were really special, and we had the chance to revamp them.

Did you end up doing any significant reworking of the songs?

Tyler: Originally, we only had two nights to record the songs, so they were pretty bare bones. Sometimes that was perfect, but I often ended up adding to the songs. It was a cool process to revisit them and to think about how they fit together on an album, almost like arranging a film score, as a work with an overarching story. We also brought in the bits of Robin’s grandmother talking on her old recordings.

Many of your songs mix traditional folk music styles and forms with more modern sensibilities. What sorts of sonic ideas informed the approach you took to writing and recording the new album?

Tyler: One of the weird things about living in a rural place and having a family is that I’m exposed to so much less here. It’s a little bit of a bubble. I don’t have the same kind of influences as when we were living in Philly. This area gets overlooked as a musical entity, so I was interested in this idea of New England music. I wanted the sounds on the album to be of this place. One of the things I had in my head was a lot of different strings and plucks and pops—I built the record up by trying out all sorts of sounds. I was mostly limited to the instruments that were in my studio up the road, and we played everything on the whole album except for the singing saw and a few horns.

Each of Vermont’s seasons has a distinct soundscape—did you try to incorporate those sonic qualities of the landscape into your compositions?

Tyler: I thought a lot about seasons. They are such a big deal up here. Living in the middle of winter is a different world than living in the summer. For some of the songs, both lyrically and sonically, I tried to get after that idea. “Silver Medallion” is specifically a summer song. It takes place on July 4th, and it’s meant to have a sort of open feeling. Winter can be claustrophobic, because you’re literally snowed in and huddled next to the stove. The sky is low and dark and grey, and it’s pressing in on you. “Cold Lunettes” is meant to feel like that.

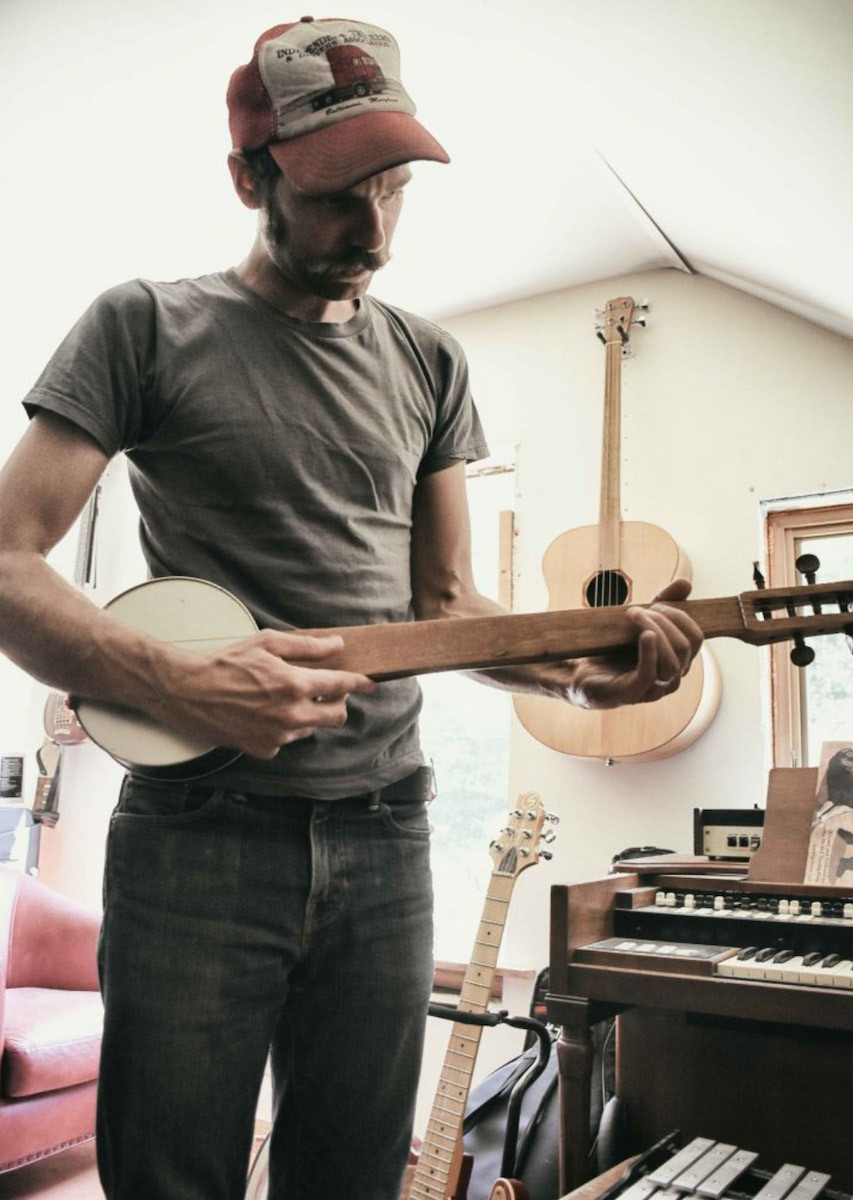

You use a lot of traditional instruments on the album—guitar, banjo, bass—but you seem to be exploring their outer spheres of timbral possibility.

Tyler: Part of it is just that I’ve played these instruments for so long, and I’m also a little frustrated with the traditional idea of what a band is—guitar, bass, drums. The Beatles did that years ago, and no one’s ever done it better. There are plenty of bands that I think are amazing, but it’s just odd that the idea of what a band is—what rock is, what folk music sounds like—doesn’t seem to change. I started thinking about isolating sounds so that they’re individual plucks instead of chords. It’s just a note, or an out-of-tune note. I did a lot of the percussion that way, too. There’s no drummer on this album, it’s just different percussive sounds. On the song “Swimming” there’s a snare drum sound, but it’s just me hitting the head of the banjo with my finger. I tuned it to an open chord in the key of the song, so it has this watery, lush sound—pwooonngg.

Robin: We also recorded some songs, like “Electric No. 4”, in the cabin, which has a bunch of broken windows and no screens. Then we recorded some tracks in my grandparents’ house, which is this 250-year-old farmhouse with creaking floors and a certain reverberation of the wood. I think that really transformed the way we thought about those little atmospheric sounds and how much texture and ambiance they could bring to the album.

Tyler: There’s a great moment in one of the songs when an acorn falls on the tin roof of our old cabin. It’s a loud popping sound, but it lined up with something in the music, so it’s like a hidden gem in the mix.

Robin: Our albums are basically studio albums at this point—we don’t plan to perform them live—so that frees us up to experiment and have fun with what you can do in a studio.

What do your kids think of your music?

Tyler: I think they think of our music as the thing that we pay attention to instead of paying attention to them. Every once in a while they’ll come out out of the blue and say something, like, “I want you guys to play a show,” and that lets us know that it’s seeping in, in a cool way.

Robin, tell me about your new book.

Robin: Half Wildis a collection of short stories, all set in a fictional town in Vermont. Now that a few people in the area have read it, I’m quickly realizing that everybody is going to assume everything in the book is biographical. It’s fiction, but it’s also a combination of what I’ve observed and what I know. My parents get it—they know what’s real and what’s not real in the book—but I am definitely going to have to make that very clear to other people around here.

As you were writing these stories, some of which have appeared in various places over the past few years, did you know that you would eventually publish them all in a single collection?

Robin: I always knew that I was going to put them together. I love short story collections that are set in one place. It’s an incredible way to write about the multiple facets of place—that’s one of the things the book is about. It shows the different ways people interpret place, how people who have been here longer see the people who have come here more recently, and how people who have come here recently see people—or don’t see people—who’ve been around longer. That’s very much a thread that weaves throughout all the stories—belonging and not belonging, and varying impressions of place.

Are there characters that recur throughout the various stories in the book?

Robin: They’re more linked by the geography. There are mountains and town names, and the same creek runs through every story. The stories are set over a span of 40 years, so there are multiple generations. If you read it closely you might recognize the grandmother from one story as the daughter in another. It’s subtle, and I don’t expect readers to pick up on all of that, but I hope it gives a sense of this place and community being interconnected.

Is the book meant to be read cover-to-cover, or can readers jump around through the various stories?

Robin: I thought very carefully about the story order, but it’s not chronological in any way.

Tyler: One of the things I really love about Robin’s book is that it reads like a novel, and place is almost the main character. I would love it if people read it from start to finish, not because it’s so linked, but because the texture is similar to an album.

Robin: During the very last edits to the book I made a few subtle connections between the stories, so those things will definitely have an impact if you read them in the order that the stories are arranged.

You’re also working on your first novel. Can you talk about it yet?

Robin: All I can say is that I wrote a first draft. My editor likes it—phew! I got a two book deal with Ecco/HarperCollins. When they accepted the short story collection, they also accepted the novel, sight unseen. They hadn’t seen a word of the novel until I handed in the draft in June.

Is there an extra level of anxiety to writing your first novel?

Robin: I had no idea how to write a novel, but I’ve also had this book simmering for five years. I had a pretty good idea of who the characters were, so it’s not like I sat down to write a novel from scratch.

Is the process of writing your novel very different from writing short stories?

Robin: I always thought that I loved short stories—that was my form. I love Alice Munro, I love Chekhov. But I also love the novel as a form. It has such capaciousness. You can fit anything in, and it can wander in all these loose directions and connect in less formal ways than short stories do. There are a million ways to structure a novel, there’s no right or wrong way to do it. Even though I knew who my characters were and what was going to happen, I spent a lot of time backtracking and scribbling notes in the book about where the story would go.

Do you have a deadline for the novel?

Robin: We don’t have a date set. It’s just been a very fun year, being able to write a novel as my job. Every morning, while the kids were in school, I sat down and worked on it. That’s an incredible dream come true and, even though I had moments of panic, I never lost sight of that.

A lot of people who live up here are interested in pursuing the “good life” that Helen and Scott Nearing promoted in their books. How are you defining the good life for yourselves here in Vermont?

Robin: I really can’t imagine raising my kids anywhere else. My mom has a farm here. My brother has an orchard up the hill. We have extended family all around us. When you grow up on a farm, surrounded by family, in a place where people make music together—to leave that behind is really hard. When it comes to having children, I can’t imagine not offering them this whole interconnection of community and place and landscape and food. It’s a pretty dark world these days, and this is a little spot of preserved heaven. I’m going to keep that innocent bubble for them as long as I can.

Tyler: Now that we’re parents, we do a fair amount of thinking about global warming and worrying about the future of our planet. Part of living the good life is trying to live a life that’s conscious of that.

Robin: This isn’t the most sustainable place—really we should all be living in cities where we can bike. We do heat our house solely with wood that’s from right here, we heat our water with solar, we get our electricity from solar panels, and we grow a lot of our own food. So, we try our best.

You’ve now put out four albums together, in addition to supporting each other on several other creative pursuits. What’s your secret to working so well together as a couple?

Tyler: Before we started Red Heart the Ticker we deliberately didn’t play together because we thought it would be too hard. We were coming at music from somewhat different angles. I studied music quite a bit, played a lot of jazz, and maybe was more technical about it. Robin just has this wonderful natural talent for music.

Robin: And I refuse to learn the names of guitar chords.

Tyler: She doesn’t like to practice. Whereas, for me, if something is beyond my reach and is challenging, I love to work on it until I can master it. We’ve thought so much about how to work together creatively. A lot of couples try to do it, and it’s hard. We’ve found that we trust each other a lot. It’s harder to take criticism about your work from your spouse than from someone who’s removed from the situation, but the criticism also means more.

Robin: The quick answer is that our way of working together is not working together. I basically quit the band. We have this latest album, but this may be the band’s last hurrah. And we won’t really be performing live shows other than this one in Brattleboro. We used to travel a lot when we just had one kid. My dad or a friend would come with us to shows, and that worked. Then we had two kids, and that just stopped working. Two years ago we signed up for a really good gig that was a couple hours away. We realized that we had to drop the kids off with my parents, and they were busy with sugaring season. It happened to be the day when they collected the most sap they ever had, and they were going to be up until midnight. They laid down little pieces of cardboard on the floor of the sugar house for the kids to sleep on, we stopped to wave goodbye, and then our car sunk down in two feet of mud. We got the tractor, and it ripped the bumper off the car. We did make it to the gig, but that was it for me. That was a sign.

So this may be the last album and live performance from Red Heart the Ticker?

Tyler: Well, never say never…

Catch Robin MacArthur and Tyler Gibbons at their book launch & album release partyat 118 Elliot in Brattleboro on Friday, August 5th. Find Robin on Twitter(@RobinMacarthur) and Instagram(@robinwoodbird), and visit her website here. Read more about Tyler’s film scoring projects on his website. Red Heart the Ticker is on Facebook, Twitter(@redheartthetick), and the web.

About the Author/Photographer:

James Napoli is the founder of Junction Magazine. James has since moved to Minnesota and all content is managed by a collective of artists. Read more about them here.